- 7.1.0Cover

- 7.1.1tl;dr part 1Editorial

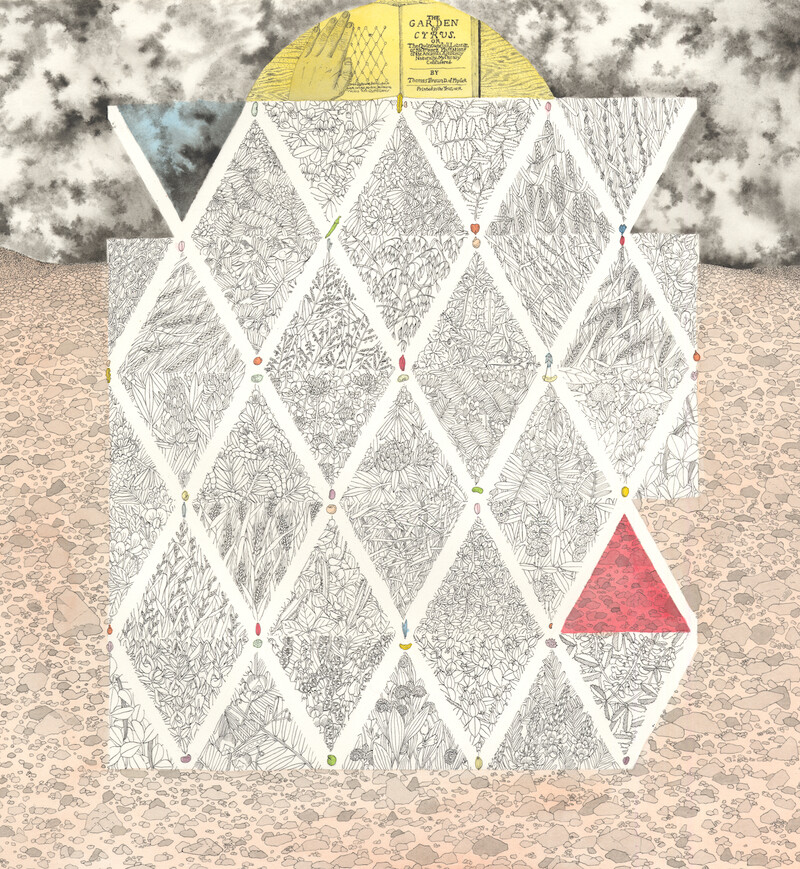

- 7.1.2Conjecture DiagramsSara Graham

- 7.1.3The Year I Stopped Making ArtPaul Maheke

- 7.1.4W.E.I.R.D.: UncertaintyNicola Privato

- 7.1.5Impotentiality and ResistanceJohn Paul Ricco

- 7.1.6Social Distancing in the Time of Social MediaChristina Battle

- 7.1.7Hold StillKimberly Edgar

- 7.1.8Alternate Forms of DeliveryAisha Ali, Atanas Bozdarov, Inbal Newman, Craig Rodmore, and Florence Yee

- 7.1.9Who Is Inside

(Your Pandemic)Amy Fung - 7.1.10amidstd’bi.young anitafrika

- 7.1.11Four Thieves VinegarSydney Shen

- 7.1.12How to Swim in a Living RoomAdam Bierling

- 7.1.13A Fever, A CrisisKimberly Edgar

- 7.1.14LifersNoelle Hamlyn

- 7.1.15A Job GuaranteeD.T. Cochrane

- 7.1.16"Deception is a co-effect which cannot be neglected"Ruth Skinner

- 7.1.17Virus and CommonsAndrea Muehlebach

- 7.1.18Quarantined Connections at the End of the WorldPaul Chartrand

- 7.1.19DistancingAlison Bremner

- 7.1.20After the RainsSanchari Sur

- 7.1.21Crisis and CritiqueEric Cazdyn

- 7.1.22Colophon

Quarantined Connections at the End of the World

The Svalbard Seed Cultures Initiative

- Paul Chartrand

At 78.2232 degrees north, deep inside the Arctic Circle, in the Svalbard Archipelago of Norway, lies the town of Longyearbyen. It is a town that has gathered growing significance over the years since the development of one of its most important sites, the Svalbard Global Seed Vault. Since opening in early 2008, the Global Seed Vault has accepted more than one million samples of seeds, with a capacity for 4.5 million varieties of crops (2.5 billion seeds in all). The vault’s location—120 metres inside a mountain, locked in permafrost—was initially chosen because of the constant -18°C temperature and nearly absent tectonic activity. Despite its seemingly apocalypse-proof site, expensive adjustments have been required to ensure the safety of the vault’s seeds through the continued escalation of climate change.11Damian Carrington, “Arctic stronghold of world’s seeds flooded after permafrost melts,” The Guardian, May 19, 2017, http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2017/may/19/arctic-stronghold-of-worlds-seeds-flooded-after-permafrost-melts. It is partly out of this sense of urgency that a new project for preservation was born.

In the same mountain that holds the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, there is a decommissioned coal mine that was once used to store seeds and genetic materials for the future. Within the very same chamber that holds the remnants of that first seed bank, there resides a collaboratively developed vault for preserving culture alongside biodiversity. The Seed Cultures Initiative is a project led and curated by Dr. Fern Wickson, who seeks to build a cultural parallel to the Global Seed Vault with a Seed Cultures Ark. The Seed Cultures Ark acts as a sort of sister archive to the Global Seed Vault, communicating the cultural connections and stories of the quiet, frozen seeds next door. Over the past two years, the ark has accumulated fifteen artworks from artists and collectives around the world, among whom I had the immense pleasure of being included. A content-rich website functions as an ongoing archive for the project, gathering “exceptional work exploring the life of seeds through art and culture.”22“Seed Cultures Archive: About,” Seed Cultures Archive, http://www.seedcultures.com/about.

The range of works interred in the mountain is as impressive as the variety of seeds in the neighbouring vault. The contributing artists are all deeply passionate about ecological and social issues concerning seeds and connections with agriculture. Among these concerns are the preservation of heirloom genetic materials, acknowledging Indigenous agricultural techniques, and esoteric spiritual connections with seeds and animism. The conceptual depth and breadth of these artworks form a testament to the importance of the issues considered.

In 2018, the first deposit into the ark included Sara Schneckloth’s mixed-media drawing series (In)Nascence, which records the early stages of seed germination as observed by the artist as she nurtured the embryos of beans. The seeds’ embryonic potential is captured in these carefully composed images, which channel imaginative and embodied relations with seeds through the visual language of scientific diagrams.

Intricate organic detail and clean geometry combine in the drawings of Mollie Goldstrom. Densely packed imagery reflects scientific, mythic, and literal interpretations and misunderstandings of human/nature relationships regarding seaweed. These drawings reflect the artist’s curiosity through her commitment to describing the visual and ecological characteristics of a plethora of seaweed species. Goldstrom’s optimism shines through her presentation of the usefulness of seaweed to societies facing environmental devastation.

The branching systems of trees, roots, rivers, and human arteries inform the colourful print-based work of Mary Robinson. Layered, repeating patterns of cellular forms and a blurring of background and foreground reference the formation of memory through lived experience. The artist’s prints and books thus become biographical records as well as reflections of biological interdependence.

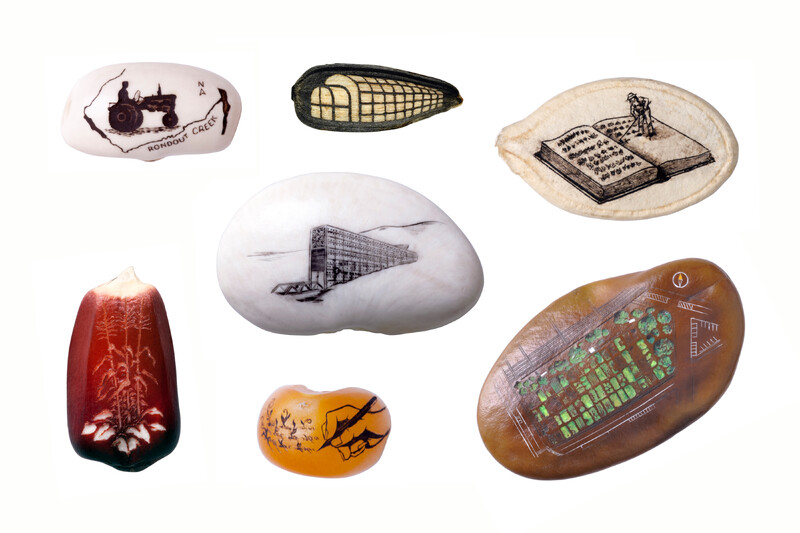

In 2019, another group of artists was invited to deposit work in the ark. Incredibly detailed microscopic engravings by Sergey Jivetin mark the seed coats of agricultural heritage varietals. The etched drawings symbolically describe the histories of those who cultivated them. The seeds are viewable through custom-made magnifier capsules, and ultimately planted to become living embodiments of their histories.

A photographic and sculptural installation by Ivan Juarez pays homage to La Milpa, a “traditional and historical agricultural system from Maya and Mesoamerica[n] civilization that produces maize, beans, squash, and chile.”33“Ivan Juarez,” Seed Cultures Archive, http://www.seedcultures.com/#/ivan-juarez/.Juarez’s work harnesses narrative, cultural, historical, and contemporary lived experiences with these staple foods, advocating for dialogue among ecology, art, and society that better represents human connections to food systems. Here, one can see that past ways of living within the natural world remain relevant in the present.

The Migrant Ecologies Project provided a strange chronicle with their contribution, which was based on a specimen from colonial Singapore’s Raffles Museum. The artist collective sifted through (gleaned) wheat-straw stuffing from a 4.7-metre-long, 133-year-dead taxidermied saltwater crocodile for a single wheat seed. They documented and presented the process in an installation that respects the spiritual significance of the crocodile, which is believed to host the spirit of Panglima Ah Chong, the Singaporean anti-colonial freedom fighter. Presented partly as a fold-out accordion map/book/guide of the entangled “legacies of colonial agro-economies and monstrous dreams of progress,” the project included many dozens of letters addressed to the “Grain of Wheat/Crocodile/Spirit.”

The contribution from the Seeds InService duo (Melissa H. Potter and Maggie Puckett) included colourful handmade paper and publications centred on the work of establishing a series of thriving heirloom gardens that serve a variety of feminist causes. The duo’s gardening and papermaking practice focuses on issues such as women’s reproductive rights and the plants used to control them, and species erased by colonial and racist domination of agriculture. Self-empowerment and collective engagement propel their work forward.

These projects, and many others supported by the Seed Cultures Initiative, expose the multitude of crises facing human and plant societies during the Anthropocene. However they also present a hopefulness that art can intervene in contemporary crises through direct social and ecological action. Through community, narrative, and direct action, the participating artists endeavour to challenge the capitalist status quo. Their works acknowledge the importance of traditional and scientific forms of knowledge, and reject corporate greed—a driving force behind large-scale industrial agriculture.

In Longyearbyen, during 2018 and 2019, some of the artists joined each other to share ideas and work. They exhibited their work at a local establishment for only a single day (measured in hours, not in the setting of a perpetually visible sun). Following the exhibition, the artists packed their work into plastic totes matching those used in the seed vault and headed to the mountain for “burial.” More than 100 metres inside an abandoned coal mine lies the roughly hewn chamber where their art will remain archived permanently. Glistening with ice formed by the breath of the artists, the room also contains the rusting container that originally housed seed deposits from around the world. After a period of silent contemplation, the totes containing the artworks were neatly stacked and left to the cold darkness as the artists returned to the light above.

In light of COVID-19 and restrictions on global travel, no deposit will be made in 2020. Dr. Wickson continues to work on this living project and hopes for another deposit in 2021. It is worth remembering that despite conditions of isolation, artists and environmental knowledge-keepers continue to work collaboratively toward care for the land and each other.

See Connections ⤴