- 7.1.0Cover

- 7.1.1tl;dr part 1Editorial

- 7.1.2Conjecture DiagramsSara Graham

- 7.1.3The Year I Stopped Making ArtPaul Maheke

- 7.1.4W.E.I.R.D.: UncertaintyNicola Privato

- 7.1.5Impotentiality and ResistanceJohn Paul Ricco

- 7.1.6Social Distancing in the Time of Social MediaChristina Battle

- 7.1.7Hold StillKimberly Edgar

- 7.1.8Alternate Forms of DeliveryAisha Ali, Atanas Bozdarov, Inbal Newman, Craig Rodmore, and Florence Yee

- 7.1.9Who Is Inside

(Your Pandemic)Amy Fung - 7.1.10amidstd’bi.young anitafrika

- 7.1.11Four Thieves VinegarSydney Shen

- 7.1.12How to Swim in a Living RoomAdam Bierling

- 7.1.13A Fever, A CrisisKimberly Edgar

- 7.1.14LifersNoelle Hamlyn

- 7.1.15A Job GuaranteeD.T. Cochrane

- 7.1.16"Deception is a co-effect which cannot be neglected"Ruth Skinner

- 7.1.17Virus and CommonsAndrea Muehlebach

- 7.1.18Quarantined Connections at the End of the WorldPaul Chartrand

- 7.1.19DistancingAlison Bremner

- 7.1.20After the RainsSanchari Sur

- 7.1.21Crisis and CritiqueEric Cazdyn

- 7.1.22Colophon

"Deception is a co-effect which cannot be neglected"11Camille Flammarion, Mysterious Psychic Forces: An Account of the Author’s Investigations in Psychical Research, Together with Those of Other European Savants (London: Small, Maynard and Co., 1907), 195. The full quotation reads: “In the experiments which we are considering in these pages, deception is a co-effect which cannot be neglected.”

- Ruth Skinner

I’m spending a lot of time reading about how psychics and conspiracy theorists are wrangling with this event.

In New Dark Age, James Bridle dedicates a chapter to conspiracy. He recounts observing the flight patterns of UK aircraft as they deported asylum seekers or carried out surveillance-gathering missions. Bridle holds these very concrete airspace activities—expulsion, spying, and their corresponding carbon impacts—alongside the suspicions of chemtrail soothsayers. “Something strange is afoot,” he writes. “In the hyper-connected, data-deluged present, schisms emerge in mass perception. We’re all looking at the same skies, but we’re seeing different things.”22James Bridle, New Dark Age: Technology and the End of the Future (London; Brooklyn: Verso, 2018), 192.

Bridle mentions GCHQ Bude in Cornwall, which Wikipedia identifies as a “government satellite ground station and eavesdropping centre.” GCHQ Bude is located near one of the first transatlantic undersea cables. Edward Snowden famously reported on its info-gathering operation, codename Tempora: a computer system that archives and observes fibre-optic communications, sharing its data with the National Security Agency. Tempora, plural of Latin tempus (“time; period”). We’re now undeniably aware of the age of information compromise, permeability, and permanence.

The town of Bude was also the final home of artist and occultist Pamela Colman Smith, who illustrated the canonical Rider-Waite-Smith tarot deck. Last year I had the opportunity to visit the house where she died, impoverished and indebted. It’s now a pub, so I ordered lunch and sat to take in its beautiful big windows, over-painted door jambs, and slot machines. Mid-bite, an electrical socket in the room emitted a snap-bang loud enough to startle everyone into silence, followed by nervous laughter. That electrical discharge feels much more prescient now: an oracular hiccup in a network of information-laden, sea-buffeted circuitry.

Electrical discharges abound in the present as telecom companies commit to uncapping our data. My sessional teaching contract, like everyone’s, has pivoted online. We’re wrapping this Digital Literacies class with a week on conspiracy. Bridle’s chapter is our reading. Artist Christina Battle gamely upholds an earlier invitation to guest lecture by organizing a wonderful remote activity and discussion. Students gather and share images of what they’ve been reading online (memes, panic-buying, news articles, their own Zoom faces). They talk through their experiences of physical distance/hyper-connectivity. It’s good to see all their faces. Battle comments that among all the information circulating about the environmental effects of COVID-19, no one seems to be speaking about the carbon footprint of the internet anymore.

The cobweb cloak of Time has dropped between the world and me,

The Rainbow ships of memory have drifted out to sea.33Verse by Pamela Colman Smith on A Broad Sheet #7, edited by Jack Yeats and published by Elkin Mathews, London, July 1902. From the website of Fonsie Mealy Auctioneers, Lot 443/0297 [SOLD]: “No limitation is recorded, but it is unlikely that more than a few hundred copies of each Broadsheet were produced and coloured. Because of its large size, very few have survived in good condition… Extremely rare,” but easily searchable.

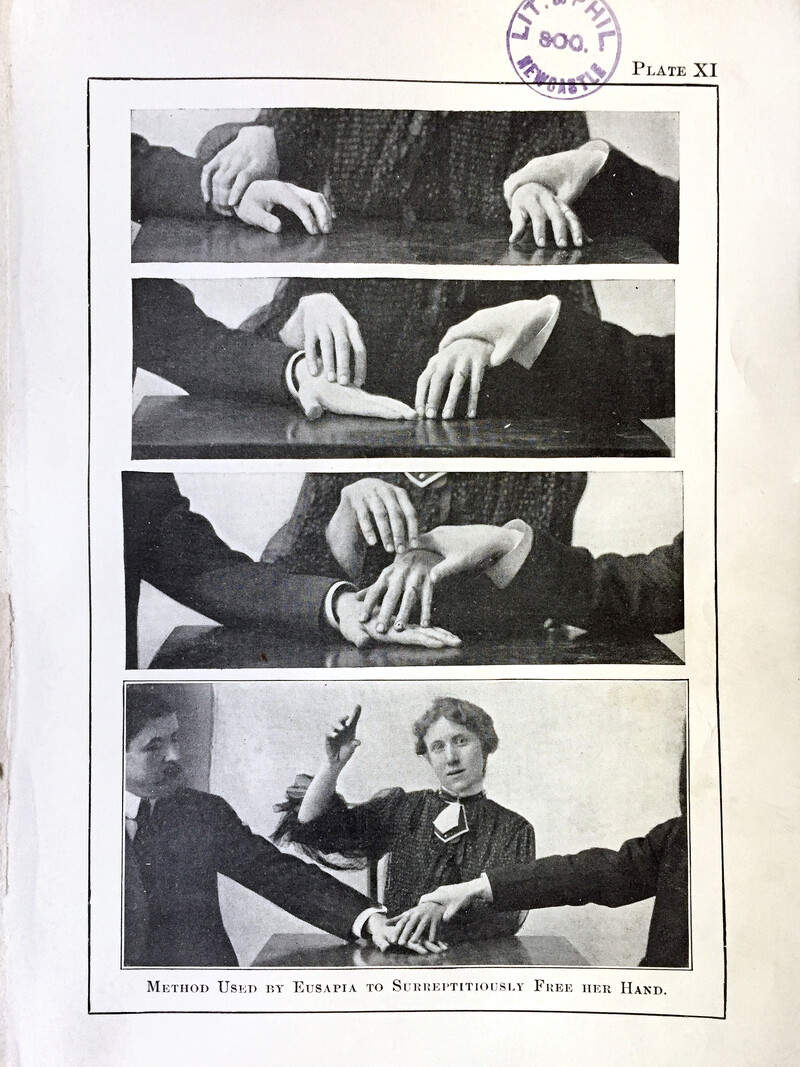

In this moment, thinking about the seemingly fraught relation between seen and unseen, natural and supernatural (and our collective inability to distinguish which is which), a series of photographs fix in my mind as potentially useful. They perform as a Rorschach test for discerning-deciding how the present is beginning to feel; they present a visual mantra for settling into that unsettling feeling. These images constitute Plate IX from Camille Flammarion’s 1907 text, Mysterious Psychic Forces: An Account of the Author’s Investigations in Psychical Research, Together with Those of Other European Savants. Plate IX is captioned: “METHOD USED BY EUSAPIA TO SURREPTITIOUSLY FREE HER HAND.”44Plate IX is inserted between pages 206 and 207 of Mysterious Psychic Forces.

I found Mysterious Psychic Forces at the Literary and Philosophical Society in Newcastle, one of the oldest independent libraries in Britain. Flammarion’s book is shelved among esotericism and parapsychology. Histories of witchcraft, tomes on spiritualism, poltergeist activities, and studies of extrasensory perception are catalogued between continental theory, to the left, and psychoanalysis, to the right. The book’s placement demonstrates the perpetual, meaningful proximity of systems and methodologies that are expected to perform distance. Nearby Flammarion is a battered copy of Henri Bergson’s 1889 thesis Time and Free Will. Somewhere between 1948 and the present, according to loan stamps, a reader underlined Bergsonian fragments on potential futures: “we shall have lost a great deal… the future, pregnant with an infinity of possibilities.”55Bergson’s passage reads in full: “Even if the most coveted of these becomes realized, it will be necessary to give up the others, and we shall have lost a great deal. The idea of the future, pregnant with an infinity of possibilities is thus more fruitful than the future itself, and this is why we find more charm in hope than in possession, in dreams than in reality.” In Henri Bergson, Time and Free Will: An Essay on the Immediate Data of Consciousness, trans. F. L. Pogson (London: Swan Sonnenschein & Co., 1910), 10. Bergson was the brother of artist and occultist Moina Mathers.

Flammarion’s Plate IX is a series of four well-lit photographs of a woman, tulle-sleeved and seated between two jacketed figures at a small table. Three of the photos are cropped close-ups of everyone’s hands, in sequence. First frame: Woman holds Examiner 1’s wrist with her right hand, Examiner 2 holds Woman’s left. Second frame: Woman’s grip on Examiner 1 loosens so her fingers can slide-nudge his hand toward her left, still captive. Third frame: Woman’s freed hand hovers over a tender three-way hold; her captive left hand performs double duty—splayed fingers hold Examiner 1’s hand in place while her wrist is still gripped by Examiner 2. In this photograph, Examiner 2 thumbs Woman’s pinky.

The fourth and final photograph is larger, an accented “ta-da!” that pulls back to show Examiner 1 (a moustached Flammarion), Woman, and the jacketed arm of Examiner 2 (still mostly out of frame). Woman’s freed right hand is held up, her fingers positioned part-ways between a pinch and an oratorical gesture of wonder. She smiles placidly but directly into the camera as Flammarion beholds the configuration of hands on the table as if to express, “There: Trickery!” The jacketed arm of Examiner 2 once again grips Woman’s wrist tightly. There is no tender thumbing.

Alongside illustrating it so, Flammarion describes Eusapia’s surreptitious technique:

The figures shown in Plate IX represent four successive positions of the medium’s hands and those of the sitters. They show how, owing to the darkness and to a skilful combined series of movements, she can induce the sitter on the right to believe that he still feels the right hand of the medium on his own, while he really feels her left hand, which is firmly held by the sitter on the left. This right hand of hers, being then free, is able to produce such effects as are within its reach.66Flammarion, 205.

Once free, the medium’s hand is used to rap, slap, and raise tables, touch other sitters, pluck industrious hairs, waft air through harmonicas, and rattle objects. We are induced.

This substitution is one of many examples of the medium’s tricky hands. And Flammarion’s images represent a useful if somewhat heavy-handed (apologies) meeting of a number of conflicting viewpoints. Investigator and medium-apparent enact an epistemological and methodological zoetrope. They animate a tense, symbiotic encounter between scientific investigation and more esoteric methodologies. And Flammarion’s entire project is very much forensic in nature: the crisp images perform as crime-scene reconstructions; throughout Mysterious Psychic Forces Flammarion documents lights brightening even as Eusapia repeatedly asks for them to be dimmed; he measures, weights, interrogates actions and objects. But Flammarion remains a believer in at least some of Eusapia’s powers. His goal is to investigate, catalogue, recreate, and thereby dismiss psychic fraud. He also dearly seeks to find and endorse what is genuine.

But more trickery! The photographed woman demonstrating the hand substitution is herself a substitution—a forensic/stage assistant. If we are meant to accept this woman as the real Eusapia, other images in Flammarion’s book undermine the substitution. For instance, we’re shown a plaster cast that fills in the concave imprint Eusapia’s face makes in putty (an auratic feat achieved without physical contact). Flammarion compares her miraculous cameo against a striking photograph of the medium in profile, her arms swallowed in heavy fabric and her chest swathed in a dowager’s lace collar. In both images, we see that the real Eusapia is older, delicately jowled and stern. There is no mention of who Flammarion’s younger, hand-modelling “Eusapia” is, or why the need for this particular hoax when the real Eusapia is so gamely prominent elsewhere.77When it comes to images of Eusapia, the most familiar (and infamous) are the photographs in which she’s levitating tables. Someone removed most of them from this particular copy of Mysterious Psychic Forces. And why not? They’re stunning to look at: four or five people crowded around a small table, trying to force it down with their hands or springing back in shock as the flash bulb illuminates a visual tangle of hovering feet and table legs. The only levitating photo left in this copy is Plate 1: “Complete Levitation of a Table in Professor Flammarion’s Salon Through Mediumship of Eusapia Paladino.” Eusapia (the real one) sits to the left, her arms taut and her hands extended over the tabletop. I wonder if she ever experienced anything like carpal tunnel syndrome. This other Eusapia could be Flammarion’s wife, or a fellow psychic enthusiast/skeptic seeking to demonstrate/debunk the practice. Perhaps it is another medium, conceding to reveal a trick of the trade. Trickier still: the third figure in this photo series, seated mostly out of the frame, remains an open question. I’m of the mind that it is a woman in a dress shirt and suit jacket, since all we see is a disjointed arm, a decidedly slim and youthful hand that knows how to tenderly thumb a pinky, and a smudge above the shoulder that could be stray plaited hairs. Regardless, this third figure, like “Eusapia,” is a functional prop, an assistant, a collaborator, a proxy.

So images meant to demonstrate a dexterous and indiscernible ruse are caught, red-handed (again, sorry), in a bit of a double standard. Something like Edwin Sachs’ popular 1885 Sleight of Hand—Practical Manual of Legerdemain for Amateurs and Others may have been on Flammarion’s radar. His photographs effect a similar guidebook quality in their clarity and poise, and the stark white background in the first three images emphasizes a serious and scientific objectivity. But the set-up collapses a bit at the end, in that “ta-da!” moment. The crisp background is a sheet tacked up behind the trio, suddenly too small to fill the larger frame. It reminds me of us all suddenly viewing ourselves anew: on remote video calls to family, friends, and students; tucked into small, personal corners of our homes or positioned strategically against prized, neutral walls; small instances of stuff in the peripheries.

What we’re viewing in Flammarion’s photographs is a forensic restaging of an event that knowingly confounds any investigative capacity. What we’re viewing on our screens is a real-time unfolding of an event that knowingly confounds any investigative or interpretive capacity. A series of staged and unstaged, intentional and unintentional swaps are taking place, all at once: the “seamless” transition of courses online, glasses of wine over Skype, and Netflix Parties to emulate warmth and physical closeness, numerous editorial warnings against texting old flames out of boredom, the effectiveness of Zoom’s hand-raise function to keep everyone from talking over each other in the work meeting. Should we not keep our hands and eyes on the medium?

The veracity of the medium, in all ways, remains a productively open question. In looking at the photographs, it is difficult to imagine that Eusapia’s famous substitution was ever successful in practice. Try it at home with two friends (if you’re lucky enough to have those at hand, at present). Is the sleight of hand convincing? Do you mind that it isn’t? Allow a moment for tender thumbing.

See Connections ⤴