- 08.0Cover

- 08.1Block Out the SunStephanie Syjuco

- 08.2How to Read this Broadsheet

- 08.3Racial Justice in the Distributed WebTaeyoon Choi

- 08.4Coded Bias: Race, Technology, and AlgorithmsMeredith Broussard, Beth Coleman, Shalini Kantayya

- 08.5Feminist Data Manifest-NoFeminist Data Manifest-No

- 08.6Artists-In-PresidentsConstance Hockaday

- 08.7The Great SilenceTed Chiang

- 08.8Elements of Technology CriticismMike Pepi

- 08.9JunkTommy Pico

- 08.10HOW ARE WE:

A SMART CONTRACTEmily Mast & Yehuda Duenyas

- 08.11Forecasted FutureD.T. Cochrane

- 08.12They are. We are. I am.Tiara Roxanne

- 08.13Glossary

Racial Justice in the Distributed Web

- Taeyoon Choi

Introduction

Distributed Web of Care is an initiative to code to care and code carefully.

The project imagines the future of the internet and considers what care means for a technologically-oriented future. The project focuses on personhood in relation to accessibility, identity, and the environment, with the intention of creating a distributed future that’s built with trust and care, where diverse communities are prioritized and supported.

The project is composed of collaborations, educational resources, skillshares, an editorial platform, and performance. Announcements and documentation are hosted on this site, as well as essays by select artists, technologists, and activists.

Distributed Web of Care

I consider the internet as an environment, a digital space where limits are imposed upon access just as in physical environments. Reflective of the society which we inhabit, discriminatory principles are embedded in the digital space through racist, sexist, and ableist ideologies and exclusionary algorithms. Jeff Chang writes in his recent book We Gon’ Be Alright: Notes on Race and Resegregation, “Segregation is still linked to racial disparities of every kind. Where you live plays a significant role in the quality of food and the quality of education available to you, your ability to get a job, buy a home, and build wealth, the kind of health care you receive and how long you live, and whether you will have anything to pass on to the next generation.” The ability to access online spaces and information can certainly be added to this list. As a disparity unfolds in the digital space, I feel a shared responsibility to intervene in these systems of exclusion, and to build a more equitable web.

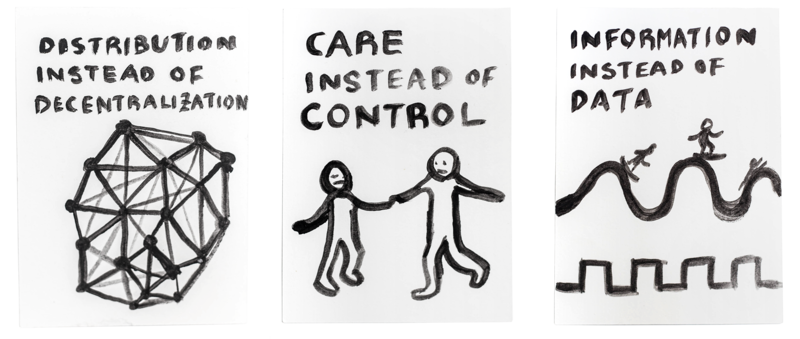

There is now a moment and opportunity to develop a different kind of internet, an internet which is more just, diverse and caring. The distributed web presents an alternative to the centralization of the big five tech companies. Similar initiatives are often referred to as the decentralized web. Although they have significant semantic and technical differences, I will group them as a family of likeminded projects for this essay. Harnessing new protocols like Dat, IPFS, SSB and various blockchain experiments, the distributed web presents a peer-to-peer model, prioritizing collective agency and individual ownership of data and code. Much like its infrastructure of autonomous nodes, the development of the distributed web is a collaborative effort, based on the community’s genuine excitement about the do-it-yourself, grassroots approach to rebuilding the web.

From my limited exposure and engagement with the distributed web communities, the developers and contributors working on the distributed web have not been ethnically or sexually diverse. Most people I interact with in real life and online have been white or light skinned, cis-gender or male, from or working in the first world countries. This is not anything new. The "internet" as we know today has been developed by white male engineers working in academia and military-industrial complexes. It’s not surprising the protocols and networks, as well as its epistemologies and affects are contained in their imaginations. To be more accurate, the internet has not been developed solely by the white male engineers, but the narratives of its development have been dominated by the triumphs of white male engineers. To learn about the queer engineers, your can read Jacob Gaboury’s A Queer History of Computing and to learn about the female engineers, you can read about Claire L. Evan’s book Broad Band. Things are changing. For example the first Decentralized Web Summit organized by the Internet Archive in San Francisco in the summer of 2018 made explicit efforts to invite people of colour, artists and creatives, and those who would not be able to afford to attend an expensive conference. While the sense of unsettling innovations, threats, opportunities were present in the conference, so were the presence of human rights advocates-lawyers, activists-community organizers, artists-storytellers. A space that’s cohabitated by various species will be mutually advantageous and more sustainable.

The Distributed Web of Care is an art project that engages this moment of technological change through performance, drawing, critical writing, and community building to address the inequalities in the internet and the power dynamics within the traditional axis of technological production. Central to this project is the question: “What kind of network do we want for the future?” In redistributing the internet’s keys (literally as unique hashes for data and metaphorically as invitations to access), and infrastructure (the fiber optic cables connecting new and obsolete electronics), there is an opportunity to redistribute power and reconfigure who can code the principles and ideologies of our technologies.

The Distributed Web of Care seeks to shift the centre of tech culture from corporations to a diverse community of technologists, artists, engineers, and scholars, holding identities across races, genders, privilege, and abilities. If the “new internet” is developed by people of color, women, queer folk, and disabled people, we can imagine new protocols and networks, untethered by the constraints which have led to these voices to remain excluded. To bring equality to access and equity to ownership of technology, we need to create new narratives of the internet, tools for learning and empowerment, and systems of interdependence among communities.

Issues of race, disability, habitat, and gender all intersect in the places we live and interact in, whether physical or digital, on the condition of access. Social media and web 2.0 has encouraged a gentrification of the internet, where information is segregated and digital labour commodified. Aria Dean writes in Poor Meme, Rich Meme about the displacement of capital in the attention economy, in which young creators of memes, most often people of colour, rarely get compensated while the tech giants profit from our engagement with these platforms. I see my practice as "networking," like weaving or knitting, where access is the fundamental building block to examine and connect the intersectionalities of race, gender, disability, and environment.

I remain struck by the song, “Do you see my skin through the flames” by artist Blood Orange, Dev Hynes. He sings,

“Tasting pain coming from a place of truth,

to be another in a messy world

to feel like giving in another turn?

You wouldn’t listen if I told you

so how can I become anyone?”

People who have been identified as an "another," marginalized people who carry "otherness," find inaccessible spaces to be hostile. They are told they can’t be anyone in that space. In order for them to feel welcome there, they need a direct invitation from the people who hold power in that space. In other words, the distributed web developers and organizations need to make active invitations to artists, creatives, policy makers, activists, organizers and those who don’t identify as developers or hold privileges to access education and technology. With a warm welcome, they can visually, sonically, empathetically redefine the distributed web. They may hold a power of queering, cripping, imagining and reverse engineering which can mend the boundaries between code and code of conduct, challenge the definitions and bring together those who saw each other as "another" or the "Other."

Take for example Roy DeCarava, a photographer who was active during the ‘60s and onward. In an article A True Picture of Black Skin, Teju Cole writes about DeCarava’s photography and its use of the commercially available films, optimized for light skin since the majority of consumers were white people preferring to look tan. This bias embedded in the technology of film led to photographs of people of color depicted with skin much darker. DeCarava uses the biased optics against itself, presenting a photograph of Mississippi Freedom Marchers in Washington D.C. in 1963, where the determination in her face is captured by the high contrast dark image. Rather than manipulate the photograph to make her skin brighter, or normalizing data, DeCarava makes creative interpretations of both the subject’s presence in the photo and the exclusionary principles of the technology.

Roy DeCarava, Mississippi Freedom Marcher, Washington, D.C., 1963. Collection of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, Robert B. Menschel Fund (1999.67.3). © Sherry Turner DeCarava/RSD Foundation.

Like the consumer film of the ‘60s, contemporary code conditions the reality to appear with biases. Our perceptions are altered by the information we have access to, and our decisions are never independent from the consciousness altering technologies. When a facial detection algorithm categorizes dark skinned person as animals, how is that different from films that render dark skinned person invisible? The most urgent task for anyone concerned with racial justice now is to acknowledge we are not living in a post-racial environment. The goal of the Distributed Web of Care is to expand the definition of "code" and "coder" to a more racially diverse, inclusive and creative definition, building resources and a community invested in a more equitable internet.

In the past ten months of the project, I’ve been learning and unlearning from my collaborators: fellows, residents, stewards and students about the web we want. I’m glad to have had opportunities to work with diverse artists and writers on the project. Many of the essays in this project are not addressing the internet directly. Instead, they explore racism, feminism, disability theory, and arts. It was my intention to fold cultural criticism with technology criticism, creating a lush garden of epistemologies and a chasm for new definitions. For example, how can we define "peer" from a social practice art perspective, from a community banking perspective and from a peer to peer protocol perspective? When the new distributed web becomes something tangible, it will be a network of various people who are generous with their talent and care. If the current distributed technologies (such as blockchain applications) start from a place of trustlessness, the distributed web of care will start from trustfulness. Let’s imagine a world of trustfulness and care, where protocols work on behalf of those who need the most support. Perhaps it will be an equitable web, an environment where people who associate in multiple racial identities cohabitate in a nurturing ecosystem. Racial justice is connected to all other aspects of justice in our environment. As Nabil Hassein, my co-organizer of Code Ecologies conference, asked, “How are all of our relationships?” in Computing Climate Change and All Our Relationships. Race, environment, and code (language, math, logic, systems and infrastructure) are connected webs of intentions, desires, hopes and needs. I think of poetic computation, distributed web and other do-it-yourself low tech alternatives such as Low-tech Magazine as small, honest attempts to create justice in the technological environment and digital space.

This text was edited by Shira Feldman and first published on the website of Distributed Web of Care, 11 January 2019, distributedweb.care/posts/racial-justice.

See Connections ⤴