- 08.0Cover

- 08.1Block Out the SunStephanie Syjuco

- 08.2How to Read this Broadsheet

- 08.3Racial Justice in the Distributed WebTaeyoon Choi

- 08.4Coded Bias: Race, Technology, and AlgorithmsMeredith Broussard, Beth Coleman, Shalini Kantayya

- 08.5Feminist Data Manifest-NoFeminist Data Manifest-No

- 08.6Artists-In-PresidentsConstance Hockaday

- 08.7The Great SilenceTed Chiang

- 08.8Elements of Technology CriticismMike Pepi

- 08.9JunkTommy Pico

- 08.10HOW ARE WE:

A SMART CONTRACTEmily Mast & Yehuda Duenyas

- 08.11Forecasted FutureD.T. Cochrane

- 08.12They are. We are. I am.Tiara Roxanne

- 08.13Glossary

Coded Bias: Race, Technology, and Algorithms

- Meredith Broussard

- Beth Coleman

- Shalini Kantayya

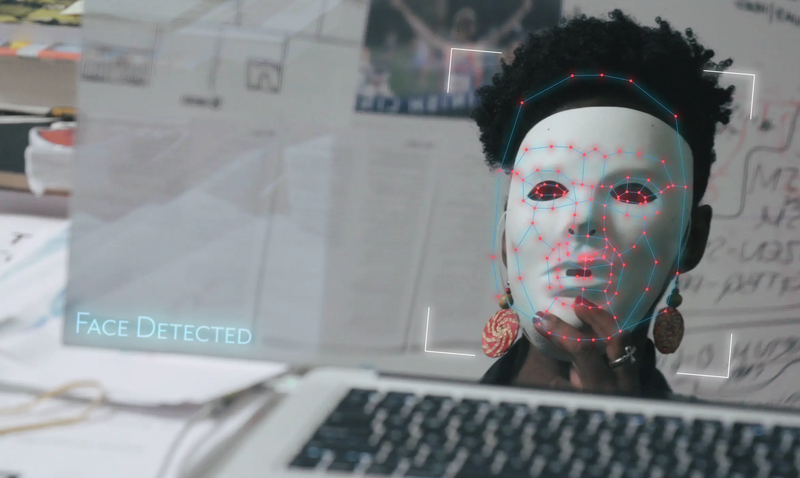

This conversation, recorded and broadcast in October 2020 as part of Running with Concepts: The Mediatic Edition, responds to the 2020 film Coded Bias, directed by Shalini Kantayya. The film explores the fallout of MIT Media Lab researcher Joy Buolamwini’s discovery that facial recognition does not see dark-skinned faces accurately, and delves into two crucial intersecting questions: What does it mean when artificial intelligence (AI) increasingly governs our liberties? And what are the consequences for the people AI is biased against?

Beth Coleman: Shalini, why make this movie? Why is this important?

Shalini Kantayya: A lot of my work has to do with disruptive technology, and whether disruptive technologies make the world more fair or less fair, and for whom. My last film explored small-scale solar as a sort of utopian vehicle for uplifting the working class and the middle class in the US. And then I sort of stumbled upon the work of Joy Buolamwini and other authors in the film—Cathy O'Neil's Weapons of Math Destruction, Safiya Umoja Noble's book Algorithms of Oppression, and of course, the great Meredith Broussard book, Artificial Unintelligence. I fell down the rabbit hole of the dark underbelly of the technologies that we're interacting with every day.

BC: Can you give people a kind of high level description of what the issue is what's at stake with Coded Bias?

SK: Everything we love, everything we care about as citizens of a democracy is going to be totally transformed by artificial intelligence—in fact, is in the process of being transformed. Not just our information systems, but things as intimate as who gets health care, who gets hired, how long a prison sentence someone serves, are already being automated by artificial intelligence. What I learned in making the film—which stands on the on the foundation of probably three decades of scholarship and activism and research, mostly by women, people of colour, and LGBTQ communities who have been speaking the truth about what's happening in Silicon Valley—is that these technologies have not been vetted for racial bias for gender bias, or even accuracy or fairness. And they exist in these black boxes that we can't examine as a society. What I began to see in the making of Coded Bias is that AI is where the battle for civil rights and democracy will happen in the 21st century.

Meredith Broussard: As Shalini said, these systems are not sufficiently audited for racial bias for gender bias. One thing that is a little horrifying to me is that these kinds of systems represent gender as a binary. And we know that gender is a spectrum, we've moved as a society beyond the gender binary. And yet, these AI systems still encode gender as a binary. So that's a really good example of how these systems do not keep up. We have this kind of myth that technology moves fast. In fact, often the opposite is true. Because what people like to do is they like to write a system that replaces human workers, and then get rid of human workers. And then there's nobody around to update the system when it inevitably needs updates. It needs updates, for fairness, it needs updates for equality. The world is not going to stop changing. Our technological systems need to keep up.

BC: If we talk about gender as non-binary, and increasingly, there's not just a rich experience, but a rigorous conversation about why that's important. Can we also talk about race as non-binary? If prediction is based on legacy, how do we think about new models of training?

MB: I have thought about this my whole life, because I identify as Black and my father's Black, my mother is white and I code as kind of racially ambiguous. The boxes that you have to check to identify yourself racially have been an issue for my entire life, because you have to choose, which is absolute nonsense, because identity is so much more than that. But this was the background that I came to computer science with. In the film, Joy Buolamwini—a really remarkable researcher—has this great moment where she's trying to build a mirror that is going to recognize her face and deliver her an inspiration every morning, and the mirror doesn't recognize her face. It's this moment where the technology has betrayed her. And she decides to investigate why.

The moment when I realized that was when I was filling out a census form, and I realized, "Oh, I'm not sure how I would count on the census." This is the moment that I go back to whenever I build technology. It's the moment that gives me empathy for people who identify as multiple things. It's also the kind of experience that is ignored by designers of computational systems. Computational systems—AI systems specifically—are mostly designed by a cisgender white men who go to elite universities and train as mathematicians and engineers. The problem is that when you have technology created by small and homogeneous groups of people, that technology inherits the conscious and unconscious bias of its creators. One of the things that Shalini's film does so well is call attention to bias and help us understand exactly how bias works in facial recognition systems, and help us understand the consequences for society and for democracy.

SK: I just want to speak to something viscerally—I was with Joy, and at MIT as sort of a camera that had facial recognition for another art project was installed. And I had the experience of standing next to Joy and the computer could see my face, and the computer could not see her face. Even in the film, I don't think it could capture how I felt in that moment, because it really felt like, "wow, um, you know, when the constitution was signed, Black people were three fifths of a human being. And here we're sitting at a computer who's looking and doesn't see Joy as a human being doesn't recognize her face as a face." To me that was this stark connection of how racial bias can be replicated. I think when you experience it viscerally—and that's not even a misidentification that comes with police, law enforcement, frisking you, or some infringement on your civil rights—just that visceral experience of not being seen has implications that we need to talk about more.

MB: And that phrase: “who gets to be human?”, or “who gets recognized as human?” is a phrase that resonates with me. Because we've put so much faith in computational systems as interpreters of the world. And yet, these systems are making judgments all the time on who gets considered to be human. It just reminds me of centuries of oppression and all of the social problems that have evolved from people not being considered human, not being considered good enough or part of hegemonic culture.

BC: I'm building on what Meredith has pointed to—many people pointed to—in terms of the homogeneity of who's in these rooms. And it's a small number of incredibly powerful companies, groups, industry groups. My question is, in addressing diversity, is it enough to have that room have different types of people in it? If we are working really, really hard to make sure that the data is diversely representative, aren't we going to be just trying to fix the problems as opposed to rethinking how we're designing the systems from the ground up?

SK: Part of the issue is inclusion. As Meredith points out, this is a small group of white men, largely under 30, that are doing this kind of work. If we have facial recognition that works perfectly on everyone, we're just going to have perfect invasive surveillance. I don't believe that the solution is having a perfect algorithm.

What's terrifying is that essentially Joy through her work at Gender Shades—and the supporting research of Timnit Gebru and Deborah Raji—points out that that systems that were not on a shelf somewhere were racially biased. This was already being sold to ICE for immigration, already being sold to the FBI, already being deployed largely in secret at scale by US police departments across the country. And somehow three scientists figured out this is racially biased, and the tech companies missed it. Just the fact that that can happen points to a hole in our society, which is: how are these technologies being deployed at scale, when they're so powerful, and have so much capacity for harm? Why isn't there something like an FDA for algorithms, something where we have to prove that it's safe, and will not cause unintended harm to people?

MB: I think we need more diverse people in the room, period. That is one fix. It's not in the entire fix for the problem. Yes, we absolutely should make our training data more diverse. But we should not deploy facial recognition in policing, because it disproportionately affects vulnerable communities. It disproportionately is weaponized against communities of colour, against poor communities. Making the algorithm better is a step and is important to do, but it doesn't actually fix the problem.

I want to go back to something that Shalini said earlier about her earlier work in in utopian visions. Thinking about utopia is so important when we're talking about technology, because the urge to say, "Okay, well, can't we just tweak this and make it better? Can't we just tweak this and make it better?" is actually a utopian fantasy. We somehow imagine that if we can make a good enough computer, then all the problems of humanity will disappear, which is such a wonderful vision, but is exactly that: a vision, a utopian vision, and is completely impractical, because there is no machine that will get us away from the essential problem of being human.

BC: When is it a great thing to not be seen by advanced automation? When is it actually a great relief to use your laser pointer or your dark skin or whatever it is knowingly or unknowingly to not be captured?

SK: Well, certainly the people of Hong Kong would say, "when you're protesting." You don't want your face to be instantly recognized and pulled up to a social media profile. The pro-democracy protesters in Hong Kong have been incredibly inventive in how they're resisting authoritarian use of facial recognition. But the truth is just that we can't opt out of a lot of these systems. And I know we're here together on zoom—it's the only way we can sort of all be together. Unless we have some laws that protect us, I feel that we don't live in a culture where we can opt out of these systems anymore.

BC: Is the legislative route one where you’re predicting good success here? I ask because I'm really moved by Cathy O'Neil's—it's not just a plea, it's a demand—that these things must be demonstrated before they can be released out into the world, before they can go to market.

SK: I am incredibly hopeful. I make documentaries because it reminds me that everyday people can change the world. I've seen that already in the making of Coded Bias. In June, we saw sea change that we never thought possible, which is that IBM said that they would get out of the facial recognition game: stop selling it, deploying it. Microsoft said they would stop selling it to police, and Amazon in a good gesture said that they would press a one year pause on the sale of facial recognition technology to police. It was brought about in part because of the integrity of the scientists in my film: Joy's work, Gender Shades, supported by Timnit Gebru and Deborah Raji, which proved this stuff was racially biased, but also the largest movement for civil rights and equality that we've seen in 50 years on the streets of literally every city across the US.

I think people are making the connection between the inherent value of Black life and racially biased invasive surveillance technologies that disproportionately impact those same communities. I owe those activists a debt of gratitude, because they have changed the way my film is received, and shown that we are ready to have a national conversation about systematic racism. When you say, “do you think it will change?” I say “yes, because we're going to change it.” I'm not saying that without effort, but I think that the biggest enemy we have is not Amazon, it's our own apathy. You know, Big Brother Watch UK: there's three young people under 30 that are preventing the rollout of real-time facial recognition by the Metropolitan Police in London. I've seen, city-by-city, people go to their town halls and say, "we know this stuff is racially biased. Can our local police departments say no? Can our colleges and universities say no?" And so, ironically, in the US, it's been the most technology-centered cities—places like San Francisco, Oakland, Cambridge, Somerville—who've been the first to ban government use of facial recognition. Because of that, we have, for the first time, a national ban on the table of government use of facial recognition.

BC: Can we build on the history of the civil rights movement? And then where we are now? Because absolutely, the streets have been, I mean—talking about disruptive technologies, guess what?

SK: The human heart on fire is the most disruptive one.

BC: One of my questions is, how do we continue to mobilize knowledge grassroots and disruption and resistance around things when, as Zeynep Tufekci and other people in the film talk about, it's so individualized? What you see on your screen is not what I see on my screen, and I got this rate for insurance, you got that rate for a plane ticket, and we feel uncomfortable, but it's really difficult at the individual level to try to trace things back to find accountability, or to say "this! This is biased."

MB: One really useful framework for this is to throw out everything that you think you know about how computers work, and to rebuild from the ground up. One of the things that I do in my book is start with how computers work. This is the hardware, this is the software. And this is how a decision is made. Once you see it at work, it demystifies it.

Another framework that I find really helpful is from Ruha Benjamin, in her book, Race after Technology. Ruha has this wonderful idea that computational systems—that automated systems—discriminate by default. So when you come into it with this understanding that these systems are not perfect, that they are discriminating somehow, and it's just a matter of shooting fish in a barrel to find the discrimination, then you have an easier time spotting it. Systems that do, for example, video analysis for hiring; they are probably discriminating against people in protected categories. The algorithms work on normative expectations about what people look like, or how people act. Say, if you have a tick, or you have Bell's palsy, or if you're blind, or the way that your body works is not in line with the normative expectations of the algorithm, then the algorithm is going to say, "Oh, yeah, that does not look like a good job candidate." Period. That's how they work. There's no mystery to it. And it's not a secret. If you go in with the frame that these systems discriminate by default, then it's much easier to spot what's going wrong.

BC: Big Brother Watch made me think a little bit also of some of the attention that was brought to the underground in London, that has both smart cards that you're swiping (so individual information about individuals), but then also smart ads that are that are targeted, and people were disrupted by this and said "this is absolutely an invasion of our privacy. This is an invasion of our civil rights." But that the system had already been put in place without any particular audit, when does that happen?

SK: The crazy thing is sometimes no one that we've elected knows it's been implemented and in motion. I think what Silkie Carlo's work shines a light on is that London has, you know, 6 million CCTVs. Meredith and I live in New York, where there are also millions of CCTVs—if those got connected to facial recognition technology, (which we don't know actually if it's been used in New York, because it's often used in secret), how dangerous that can be. For me, the big wake-up call was when I was watching Joy testify in the US Congress, and Jim Jordan, who's a very conservative, Trump-supporting Republican sort of says, "Well, wait a minute. 117 million Americans are in a face database that police can access without a warrant. And there's no one elected that's overseeing this process?"

BC: Meredith, are values of democracy going to be help us in moving forward on this?

MB: I certainly hope so. We need all the help we can get. I like what Shalini points out that fear about facial recognition and horror about facial recognition is a bipartisan issue. That bodes well for being able to stop the insidious spread in the United States.

BC: But with the pandemic, and the design around contact tracing, and other ways of bringing technology into play—particularly in light of the uprisings that have been going on through this pandemic—isn't there already a rolling out of "let's throw more technology at this problem"?

MB: I think we should stop and consider what is the right tool for the task. Sometimes the right tool for the task is a computer and sometimes it's not. In the case of contact tracing, for example, people imagine that you're going to be able to get everybody in the world with the same app on their phone. Then the app is going to just magically keep track of where you are all the time. Then it's going to magically generate a list of who you've been in contact with. And in practice, it falls apart completely, because the technology does not work as well as anybody imagines. We can't expect computers to be magic. We can't expect them to do more than they actually can. People need to get educated and feel empowered about what computers can do, and need to understand what computers can't do, and get comfortable with the idea that there are limits. So I think one of the things that the film does really well is it shows us how facial recognition really works. And it introduces us to some people who are advocating for there to be limits to what we expect computers to do in the world.

See Connections ⤴

Beth Coleman researches experimental digital media, and specializes in race theory, game culture, and literary studies. She is currently working on two books and has previously published Hello, Avatar: Rise of the Networked Generation, a critically acclaimed book examining the many modes of online identity and how users live on the continuum between the virtual and the real. She has also curated numerous art exhibits and media installations within North America and in Europe. Her current research investigates aspects of human narrative and digital data in the engagement of global cities, including aspects of locative media, mobile media, and smart cities.

See Connections ⤴

Filmmaker Shalini Kantayya premiered Coded Bias at the 2020 Sundance Film Festival. She directed for the National Geographic television series Breakthrough, which was broadcast globally in June 2017. Her debut documentary, Catching the Sun, premiered at the LA Film Festival and was named a New York Times "Critics’ Pick." Catching the Sun was released globally on Netflix on Earth Day 2016, with executive producer Leonardo DiCaprio, and was nominated for the Environmental Media Association Award for Best Documentary. Kantayya is a TED Fellow, a William J. Fulbright Scholar, and an Associate of the UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism.

See Connections ⤴