- 14.0Cover

- 14.1How to Read this Broadsheet

- 14.2Charming Life/Troubling DeathShan Kelley

- 14.3"Every Death a Policy Failure": The Other Public Health CrisisMatthew Bonn

- 14.4Queer Collectivity in the Echoes of the Dance FloorCraig Jennex

- 14.5Nowhere to IsolateRasheen Oliver, Kimone Rodney, Mya Moniz

- 14.6Questions Of, For & About ConsentWhat Would an HIV Doula Do?

- 14.7Puerto Rican Harm Reduction is EverywhereTamara Oyola-Santiago

- 14.8La Reducción de Daños de Puerto Rico está en Todas PartesTamara Oyola-Santiago

- 14.9An Army of the Sick Can’t Be DefeatedBrothers Sick

- 14.10Gesture toward JusticeFady Shanouda, nancy viva davis halifax, Karen K. Yoshida

- 14.11Start Slow, Feel the Vibrations in Your GutMourning School

- 14.12A Good DeathSarah Bird, Rayne Foy-Vachon, Kayla Moryoussef, Chrystal Waban Toop

- 14.13The Corpses of the FutureLynn Crosbie

- 14.14On the Incommensurability of Police and Harm ReductionJeffrey Ansloos, Karl Gardner

- 14.15Crises of Visibility: The Activism of MDsEmily Cadotte

- 14.16Glossary

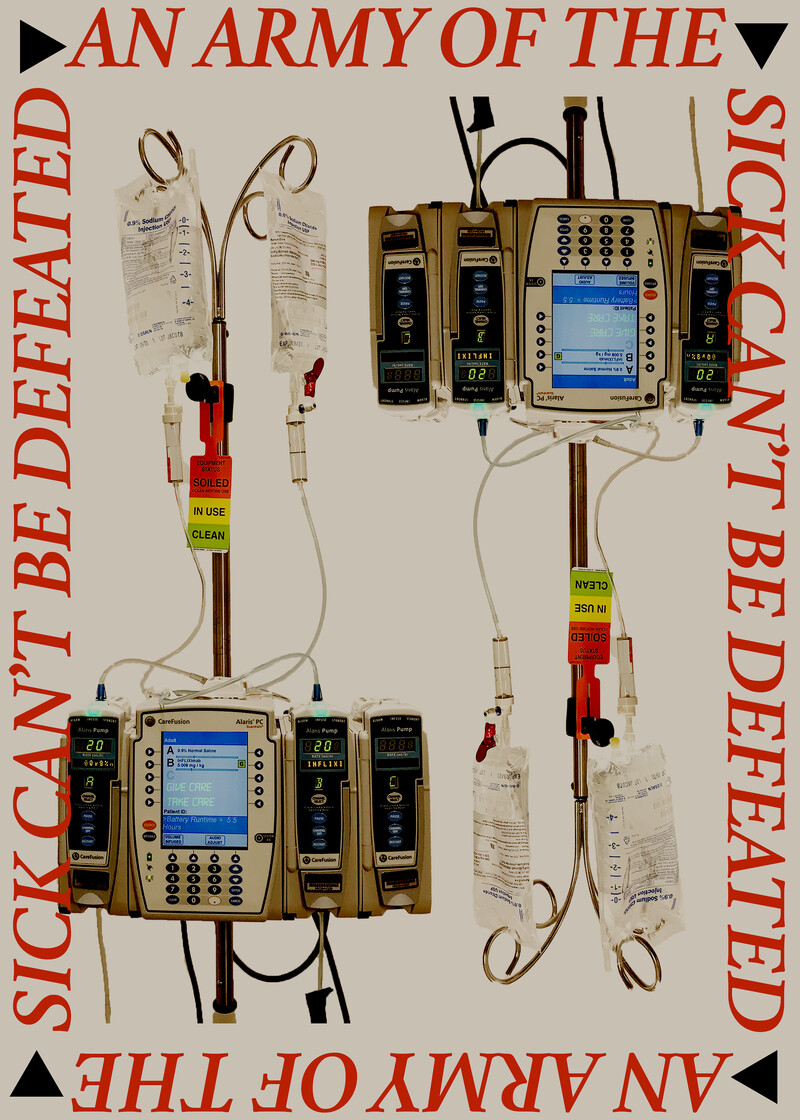

An Army of the Sick Can’t Be Defeated

- Brothers Sick

“AN ARMY OF THE SICK CAN’T BE DEFEATED”—printed in red capital letters and repeated—frames a pair of intravenous medical devices. At each corner of this border, black triangles buttress the phrase as an unrelenting gesture to pay attention. Together, this diction and series of triangular emblems recall the coalitional ethos and visual language established by LGBTQ+ activist groups, such as ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power), who in the 1970s reclaimed the pink triangle to underpin a similar rallying cry: “An army of lovers cannot lose.”11“Queers Read This,” ACT UP NY, June 1990, https://actupny.org/documents/QueersReadThis.pdf. Brothers Sick cite artist Gregg Bordowitz, who recalls this phrase when he says, “an army of the sick cannot be defeated,” in conversation with Corrine Fitzpatrick at the performance-lecture Gimme Danger, presented at Triple Canopy on March 28, 2018: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P0a6sT3ZOsQ. Carrying forward these legacies, Brothers Sick—a collaborative art project by siblings Ezra and Noah Benus—juxtapose text with images drawn from their personal archive to centre the collective and often stigmatized experience of the chronically ill, disabled, and queer communities of which they are part.

Brothers Sick forge alliances across time and space in An Army of the Sick Can’t Be Defeated, calling for participation in mutual aid and movements for health and disability justice. Reminders to “GIVE CARE” and “TAKE CARE” transmit as neon blue messages across the screens of two IV monitors, the right of which is inverted. The parallel apparatuses, carrying medication bags, tubes, tags, and other medical equipment, suggest embodied experiences of healthcare through their connection to and nurturing of the body. Creating an echo and doubling effect, the duplicated IV instruments allude not only to the multiplicity of disability experiences and the interdependency needed within systems of care, but also to the reciprocal practice of the artist duo’s collaborative work.

The intravenous therapy seen in An Army of the Sick unfolds as remnants in A Sign To Linger. Capturing the discarded IV kits, the mirrored composition of undulating cylindrical tubing and fluid solution bags within a disposal bin becomes an acknowledgment of harmful ableist practices, which undervalue and abandon sick and disabled bodies. Obscured and grainy like a photocopy, the black-and-white image evokes the abstract quality of medical imaging, such as MRI scans and X-rays, while the entangled refuse emulates the contours of a seated human figure. Breaking the image’s symmetry, two scroll-like pages, one in Hebrew and the other in English, are inscribed with a verse found in tefillin.22Part of Jewish prayer rituals, tefillin is a set of two black leather boxes that contain prayer scrolls. Worn on the head and arm, the boxes are secured by leather straps that are tightly wrapped around the arms and hands. Embracing their Jewish heritage, Brothers Sick join the long tradition of midrash—the practice of Torah interpretation done in hevrutah, with study partners—to reconceive the intergenerational prayer ritual through the lenses of illness and disability. Drawing affinities between the markings left on the body by the tefillin and IV insertion, A Sign To Linger ruminates on the enduring practices of activism and social justice that bind us in community and resistance.