- 09.0Cover

- 09.1Because You Know Ultimately We Will Band A MilitiaXaviera Simmons

- 09.2How to Read this Broadsheet

- 09.3Four Movements of DiffusionSophia Jaworski, Zoë Wool

- 09.4Water Filtration System: Floating University BerlinKatherine Ball

- 09.5Looking for a CureIrmgard Emmelhainz

- 09.6Theory of IceLeanne Betasamosake Simpson

- 09.7Legible Motivations: "Not Everything is Genuine"Nehal El-Hadi, Mark V. Campbell, Elicser Elliott, Charles Officer

- 09.8As if our Future Past Bore a Bad AlgorithmLiz Howard

- 09.9The Neurocultures Collective: Co-creating Moving Images

- 09.10ReceiptsImmony Mèn, Lilian Leung

- 09.11Weaving a Local, Grassroots WebJoy Xiang

- 09.12The First ChapterJacob Wren

- 09.13Glossary

The Neurocultures Collective: Co-creating Moving Images

In 2019 and 2020, a number of film workshops were held in the UK and online as part of a research project titled Autism through Cinema, led by film archaeologist Janet Harbord and artist-filmmaker Steven Eastwood. It was not autism under the microscope in these workshops, but rather the cinema itself was placed in the laboratory, its norms dissected. Workshop participants from the neurodivergent community considered the cinematic face, body proxemics onscreen, and event boundaries. Eye-tracking technology—often used in testing the perception and attention of autistic individuals—was reverse-engineered to reveal how a normative cinematic operation conditions the way the viewer looks and sees. Backgrounds and peripheral details were given status beyond the intentions of the source films, through enlarging and reframing film images. Interventions were made into existing film soundtracks in order to privilege environmental sound over insistent dialogue and score. Through this process, the assumed neurotypicality of the cinema came into focus, with its reliance on economies of body gesture and comportment, inferential shortcuts, and orthodoxies of social interaction configured around the emoting face.

The shared findings of the Autism through Cinema events established that autism—along with so many other marginalized ways of being in the world, and our many attention differences—cannot be encountered within existing cinematic forms. An alternative moving-image language needs to be parsed, highlighted, invented. One that does not look at autism through the neurotypical gaze but expresses itself as neurodivergent experience.

The workshops were designed to act as building blocks toward the formation of a neurodivergent community of people, whose ideas, experiences, and skills would come together in the co-creation of film practice. The Neurocultures Collective, formed at the end of 2020, comprises seven autistic artists: Sam Ahern, Georgia Bradburn, Benjamin Brown, John-James Laidlow, Robin Knowles, Anupama Mann, and Lucy Walker. The collective is collaborating with Steven Eastwood to devise and make a feature-length film, the working title of which is Neurocultures, and a multiscreen gallery installation titled STIM CINEMA. One shoot, two artworks.

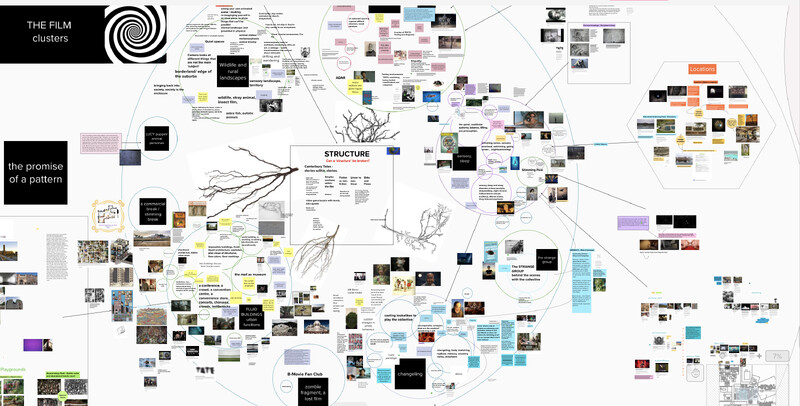

The co-creation process has adopted a range of platforms and methods, including notation involving diverse media and, owing to distancing requirements under the COVID-19 pandemic, online visual collaboration through MURAL—a platform that lends itself to visual rather than textual thinking. An outline has emerged, one that resists classification and instead offers a series of interlinking sequences, films nested within films, spiralling into and through each other. The content reflects a number of the co-creative group’s key concerns, which include masking and camouflage; critiquing the psychological structures that inform testing and diagnosis; rewilding social spaces with eradicated gestures; shape-shifting states; stimming;11Stimming is the practice of physical repetition as a way of expressing or alleviating anxiety, or simply taking sensory pleasure in recurrence. pleasure in repetition; and fascination in recurring patterns, such as the spiral. This kind of circularity and recurrence is in the DNA of the moving image, beneath its stories and temporal chronologies. Nineteenth-century photographer Eadweard Muybridge’s moving-image experiments are like prototype GIFs. The actualités of the early filmmakers the Lumière brothers prompted return visits by early film audiences to view the same single shots. As far back as the zoetrope, introduced in the 1830s, humans have displayed the desire to see an action repeatedly conducted and completed.

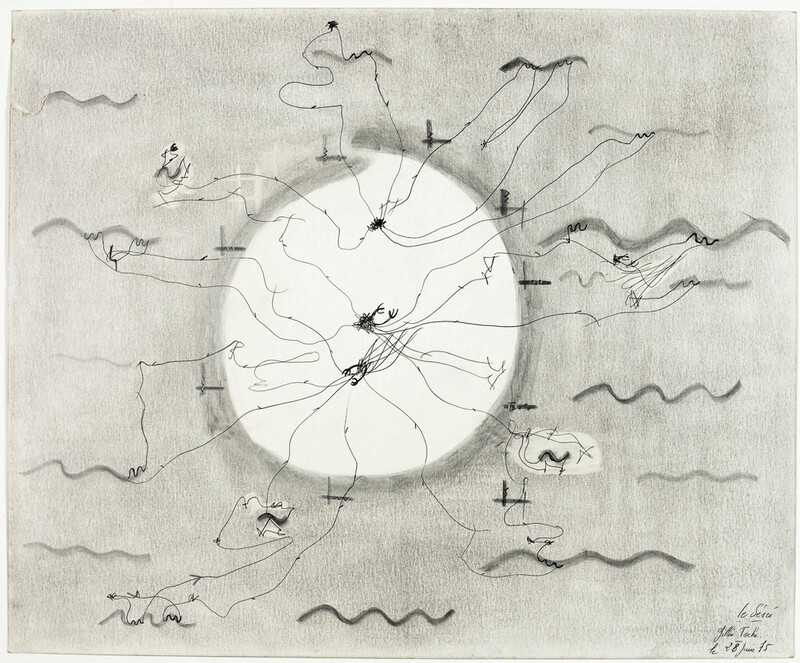

The Collective’s murals have become topographies, landscapes to glide over, but in their detail they have been cultivated as flowers, with propagating spores, image seeds, radiating petals, and extending roots. Each flower is a concept formation, pollinated by collective members as they hover across clusters, picking up and dropping associations, discourses, images. The form of the spiral in particular has enabled an arabesque in thought. In one cluster: a network of balances and imbalances, propositions for images that swing, rock, rotate, stim, and the ear canal, itself a spiral. In another: the convenience of the convenience store and the conventions of the convention centre are questioned, with liquid buildings rushing in as solutions to the crowds and cacophonies emblematic of the old normal that we might resist returning to, rather than long for . . . Spin classes, liminal spaces, bots, rotating rooms, aerial views of civic traps and escape routes, exploded architectural views envisaging sensorially-pleasurable buildings, synthetic landscapes of societal possibilities, slow buildings, quiet spaces. In a third cluster: zoological perspectives on the human species, metamorphosis and meltdown, insects and ecosystems, becoming a stray animal, the drifting camera, a film with no centre . . .

The process of co-creation has cultivated its own unique methods, working with slowness and deep listening, and continually reframing how art happens collectively. This reciprocal process makes hierarchies level, and deliberately intervenes in cultural and social acts of “looping”—philosopher Ian Hacking’s term for the effects of the classifiers, classification, and classified on each other—in this case, how autistic readings of expert models, for example, theories of mind, can give rise to resistance and change. The methodology also borrows greatly from the radical frameworks of other organizations and thinkers. These include collaborator Project Art Works, a charity based on the south coast of the UK that works with neurodivergent artists to develop a process-based, tactile, material studio practice—a sharing in mark-making receptive to the inclinations and movements of those working within and outside verbal language; and the Participatory Autism Research Collective, established in 2015 by autistic scholar and activist Damian Milton and others to build a network through which those wishing to see more significant involvement of autistic people in autism research can share knowledge and expertise. The Neurocultures Collective also takes inspiration from the anti-psychiatry of pedagogue Fernand Deligny and his concepts of “primordial communism” and “lines of flight.” Deligny’s free-associative, linguistically plastic terms—which came into being as a result of living in communes in France for autistic children and young adults, and working with the residents there—include the “Arachnean,” or the network as a mode of being. The spiralling mural clusters produced by the Neurocultures Collective resemble not only wildflowers but spider’s webs . . .

See Connections ⤴