- 12.0Cover

- 12.1Seams of ResilienceHangama Amiri

- 12.2How to Read this Broadsheet

- 12.3In Errors We See OurselvesTheodore (ted) Kerr

- 12.4The Pain that Bonds UsRula Kahil, Laila Omar, Neda Maghbouleh

- 12.5Undocumented: The Architecture of Migrant DetentionTings Chak

- 12.6carverCecily Nicholson

- 12.7"Holding the Door Open for Change"Tehmina Ahmad, Kori Doty, Gabrielle Griffith, A.J. Lowik, Nat Raha

- 12.8Epistolary LifelinesMercedes Eng, Kriss Li

- 12.9Palestinian Children: Art Therapy and Intergenerational TraumaRehab Nazzal

- 12.10Diasporic DumplingsAmanda Huynh

- 12.11Solidarity as a Force

Karie Liao

- 12.12Weaving to Reclaim the Bonds of Culture and LandNadia Kurd

- 12.13Glossary

Epistolary Lifelines

- Mercedes Eng

- Kriss Li

Mercedes Eng, a poet and writer, and Kriss Li, an artist and organizer with the Prisoner Correspondence Project, were invited to become temporary penpals to discuss solidarity-building inside and outside of prisons. Their contribution comprises letters exchanged in late winter 2022.

Dear Kriss,

It feels weird to sit down to write this letter. Letters were a main mode of communication with my father who was incarcerated for over half my life, until he died in the 1990s overdose crisis when I was twenty-two. I hated having to write these letters my mother forced me and my sibling to write. Home life was better when he was gone/inside because he had substance abuse problems that made our home unsafe, and I didn’t care about maintaining contact with him. The letters he sent embarrassed me because of his grammatical errors. He would write “I loves you guys,” not “I love you guys.” Later I would become a college instructor and learn the language of “subject/verb agreement,” enacting grammatical tyranny on my non-native English-speaking students, at the time mistakenly believing that marking all of these errors would illustrate to the students that they weren’t yet ready for this level of study when in fact it was me that needed to rethink the requirement of Standard English. As a kid I didn’t have the language of subject/verb agreement, couldn’t say his verbs didn’t match his subject, his subjugated subject. I couldn’t understand then the forces of colonialism and racism, and how they intersected with his mental health issues. I now treasure these letters as my time with my father was limited.

The organization you work with, the Prisoner Correspondence Project, is so urgently necessary, connecting lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and Two-Spirit people inside to queer folks on the outside. I mean, all prisoners need letters to connect them to the outside. But these prisoners face the horrors of incarceration, as well as sexual and gender identity-based discrimination. The last time I visited my father inside was at Matsqui, the weather was mild and we were outside walking. We passed a transwoman inmate walking with some visitors, and she waved to us, she had such a warm pretty smile. I said hello as did my dad, but after we passed them, he muttered “bug” under his breath. So it was in a prison context that I learned of his transphobia. This was the early 1990s, I don’t know what kinds of resources the woman would’ve had access to. I wonder if she had someone to write her letters, someone to throw out epistolary lifelines. What’s it been like exchanging letters during the pandemic? Was it even possible?

I’m sending along a lil strawberry painting I did after working in the strawberry field for a couple of summers at a farm operated by formerly incarcerated people.

take care,

Mercedes

Dear Mercedes,

Thank you for your letter. It’s nice meeting you this way, though I admit my roommate had two of your books and I looked at them after signing on to this correspondence. So I knew a bit about your history with your father.

Do you remember what you would tell him in those dutiful letters? Did you feel the pressure to display a “normal” family relationship when you wrote?

I’ve had trouble with subject/verb agreement myself. In 1998, at age ten, I moved from China to the inner suburbs of Toronto. I learned to speak and think in English by talking back to the TV. Those first few years were a blur, but I know I wrote lots of stories at the time. I wish I still had access to those texts. They must have contained the contorted grammar of an ESL brain, which I had worked vigilantly to overcome. Nowadays I edit the writing of people who have known English their whole lives. Meanwhile, the language I learned at birth is largely forgotten.

Grammar is a barrier for our work at the Prisoner Correspondence Project. When a prisoner gets involved, we ask them to write a self-description that we post in a public database. Outside members primarily choose their penpals based on these little bios. Sometimes prisoners who aren’t capable writers spend years waiting for someone to pick them.

As collective members of PCP, we’ve struggled with how to portray the penpal project to people outside. On the one hand, letter writing is about developing a personal relationship with someone, like making a new friend. In that case, yes, someone whose writing is hard to understand can be difficult to connect with. And in that case, someone who pushes boundaries or says offensive things—issues we see not infrequently in penpal relationships—isn’t a person outside members usually choose as a companion. On the other hand, we’re also a solidarity project to bridge the gap between communities where lots of people go to jail and ones that just know prisons as a vague concept. This gap isn’t only geographic, two sides of a prison wall. There’s also often a lifelong gulf in economic access, education, mental health, experience with violence, and all sorts of disparities that make it hard for people to talk to each other. So we usually encourage outside members to push through their discomfort, even when tough dynamics emerge in correspondences.

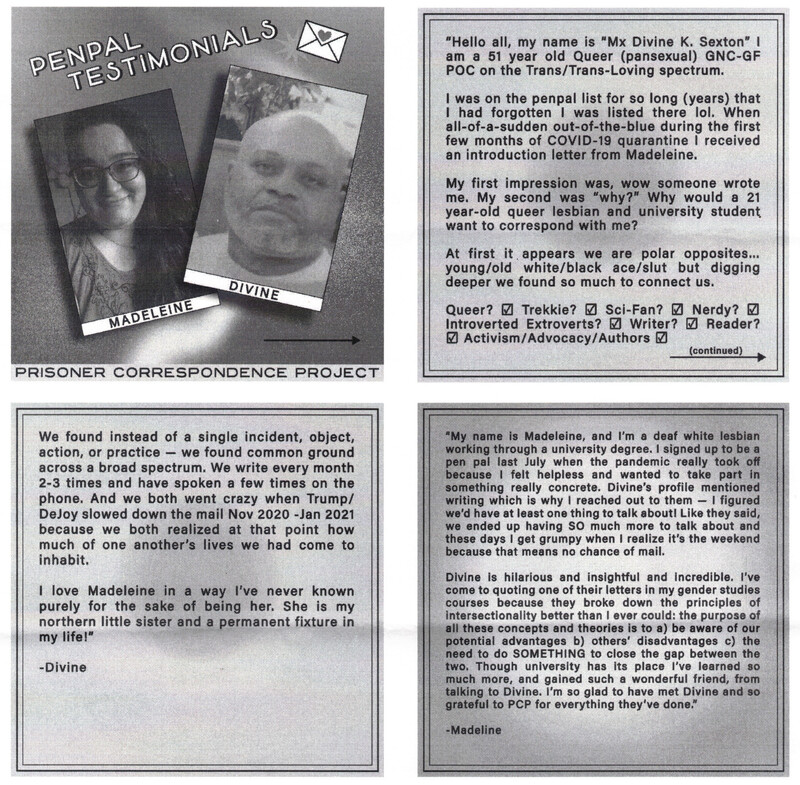

Anyway, I don’t want to make it all sound hard. Meaningful, long friendships have come out of the project. I’m including a few testimonials we've been posting on social media to get more penpals (graphic design by Sam Garritano).

Take care,

Kriss

Dear Kriss,

Thank you so much for your letter! I feel like the dutiful letters I wrote to my dad were about everyday stuff like school; or if I was off from school for summer vacation, counting down the days till we would visit my grandma and aunties in Vancouver, a sleepover with a friend, Christmas presents if it was Christmas. A few of the letters are written on Snoopy stationary that I got in my Christmas stocking. In one of them, I list what we had for dinner: roast beef, potatoes, cream corn. I remember my dad saying that a kitchen job was the best job to have in prison because you have (more) access to better food. Food insecurity in prisons is still a problem. In another I wrote out a couple of poems:

In youth we learn

In age we understand

Love is only chatter

Friends are all that matter

I have no idea where the poems are from—my grandma’s Reader’s Digests?—and what shitty “poems”! But the point was communicating, an insider connecting to an outsider.

I’m sad to hear that your first tongue is mostly forgotten. My mother said she didn’t want my father to teach us Chinese because she wouldn’t be able understand what he was saying, and she was concerned about what he might say. I’ll not address that illogic, which needs a lot of unpacking, but I was denied a significant part of my cultural heritage. My baby Chinese is come here; let’s go, hurry; I love you; thank you, how are you, and I can count. Now we’re both working in the field of writing, in English. Do you think you’ll come back to the language more fully?

Thank you for sharing about the challenges PCP faces regarding insiders who struggle with writing, who can spend years waiting on a penpal, the challenges of how to build a bridge with someone whose writing is hard to understand. And also how the distances between lived experiences can impact the germination of penpal relations. But the penpal testimonials that you sent! What a balm, what a joy to witness the solidarity between insiders and outsiders who are connecting over gender studies and queer theory, connecting over whatever, but connecting.

take care,

Mercedes

Dear Mercedes,

Thank you for sharing the things you sent your dad. When I think about intimacy, my mind goes to those rare moments when I’ve shown someone the most private sides of myself. But I feel like intimacy is often more quotidian than that, an experience of ongoing company. I hope the details of your days helped your dad feel close to you.

Your list of dinner items reminds me of a message PCP once received. An inside member calling herself “Tranny Granny from GA” thanked us for our summer 2019 newsletter, which featured prisoners writing about their food. She had shared the publication with her warden, who was so moved by the contents that he added peanut butter sandwiches to the three days every week that didn’t serve lunch. He also made a special order for the Fourth of July. Tranny Granny catalogued the feast that day: 1 LARGE pepperoni + cheese pizza from Little Caesars per person, plus free world angus beef burgers, hot dogs “grilled” with buns, chili. I mean, it’s fucked up that they had so little food to begin with but I’m glad we helped in some way.

Honestly, these days I hate speaking Chinese. I can barely express my thoughts and it makes me feel five years old. It’s an obstacle to developing an adult relationship with my mom. But I understand enough to catch the gist of most movies, and sometimes the sound of certain words will activate ancient feelings in my body that I hadn’t realized were there. I wonder whether you would’ve felt connected to Chinese as a kid if you’d been taught. Or would it have carried a trace of embarrassment, the way it did for me in the aftermath of immigration?

This has been a nice way to connect with someone new. I appreciate getting to know you.

Take care,

Kriss

See Connections ⤴

Kriss Li is a multimedia artist who creates fictional narratives, animations, documentaries, and installations that explore structures of power and the hidden sites of possibility that we can exploit towards greater collective capacities. Kriss’s practice is informed by community organizing, especially at Prisoner Correspondence Project, a volunteer-run solidarity initiative for LGBTQ prisoners. Kriss was born in Chengdu, China, and currently lives on the unceded territories of the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam), Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish), and Sel̓íl̓witulh (Tsleil-Waututh) Nations.

See Connections ⤴