Audio Description

RA Walden, ẍây ithřa: a pledge, site: Z1, audio description, 04:45. Courtesy of Rebecca Singh.

RA Walden, ẍây ithřa: a pledge, site: Z2, audio description, 04:44. Courtesy of Rebecca Singh.

RA Walden, ẍây ithřa: a pledge, site: Z3, audio description, 04:41. Courtesy of Rebecca Singh.

RA Walden, ẍây ithřa: a pledge, site: Z4, audio description, 05:05. Courtesy of Rebecca Singh.

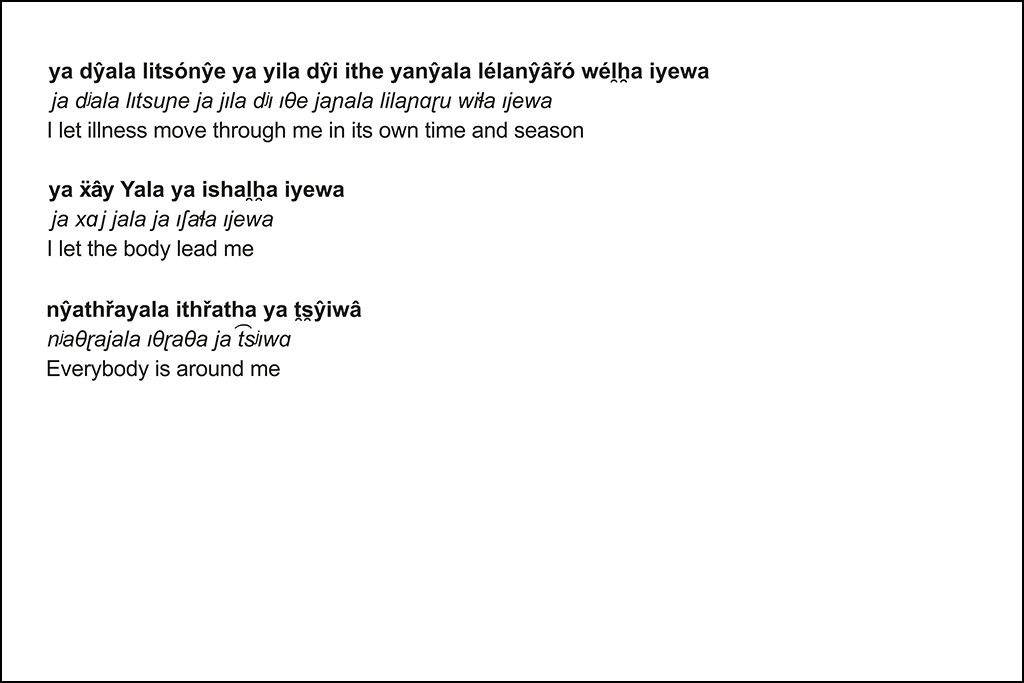

RA Walden, ẍây ithřa: a pledge (excerpt), site: Z1, 2021. Image courtesy the artist.

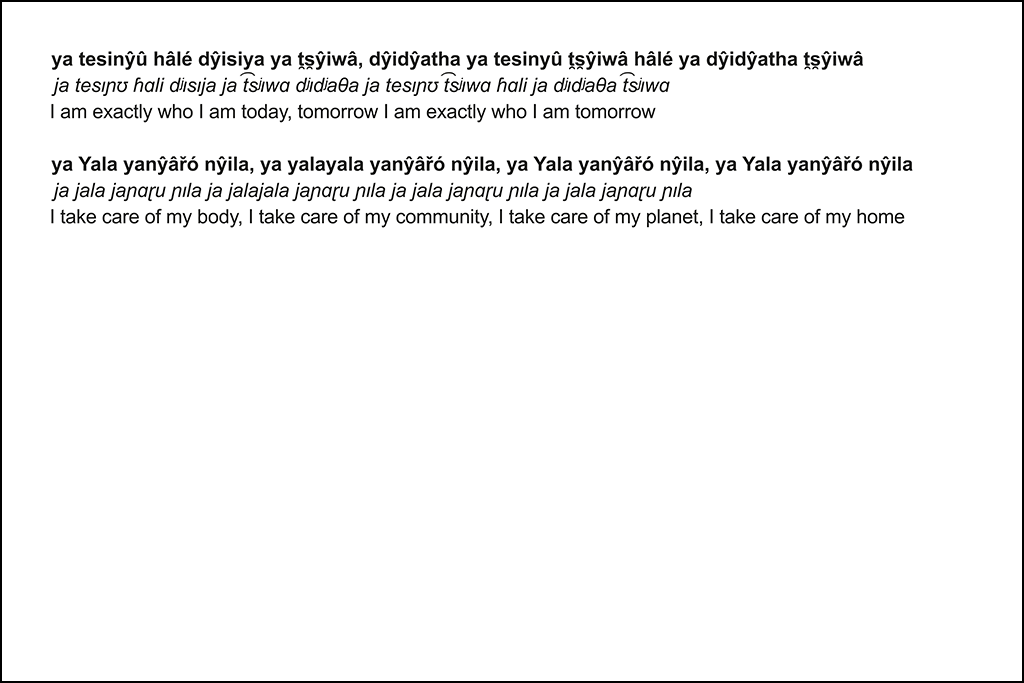

RA Walden, ẍây ithřa: a pledge (excerpt), site: Z2, 2021. Image courtesy the artist.

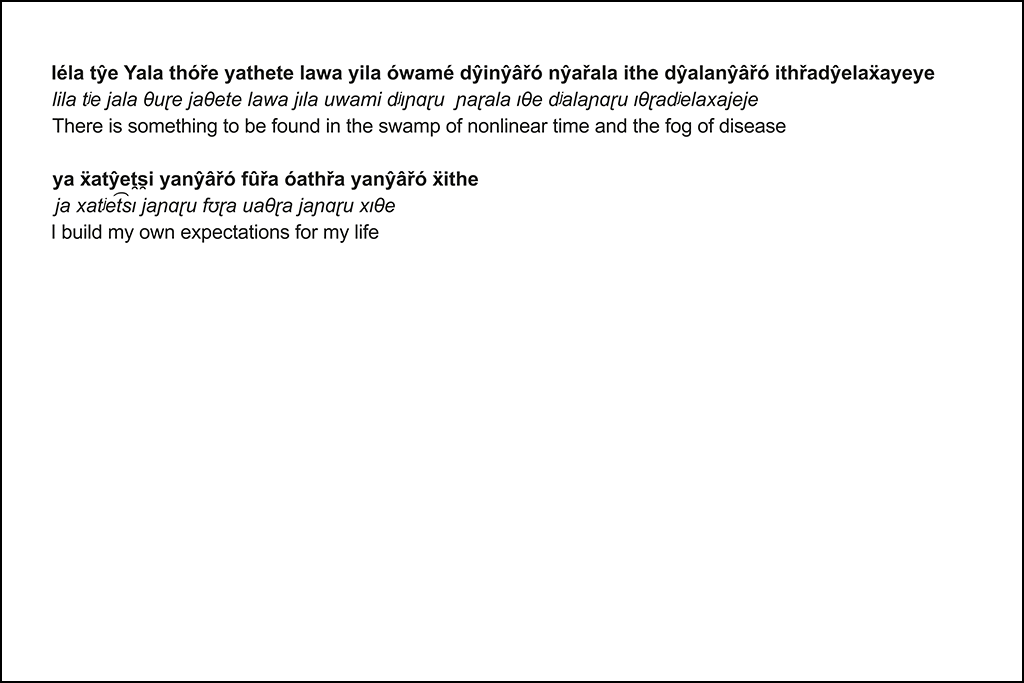

RA Walden, ẍây ithřa: a pledge (excerpt), site: Z3, 2021. Image courtesy the artist.

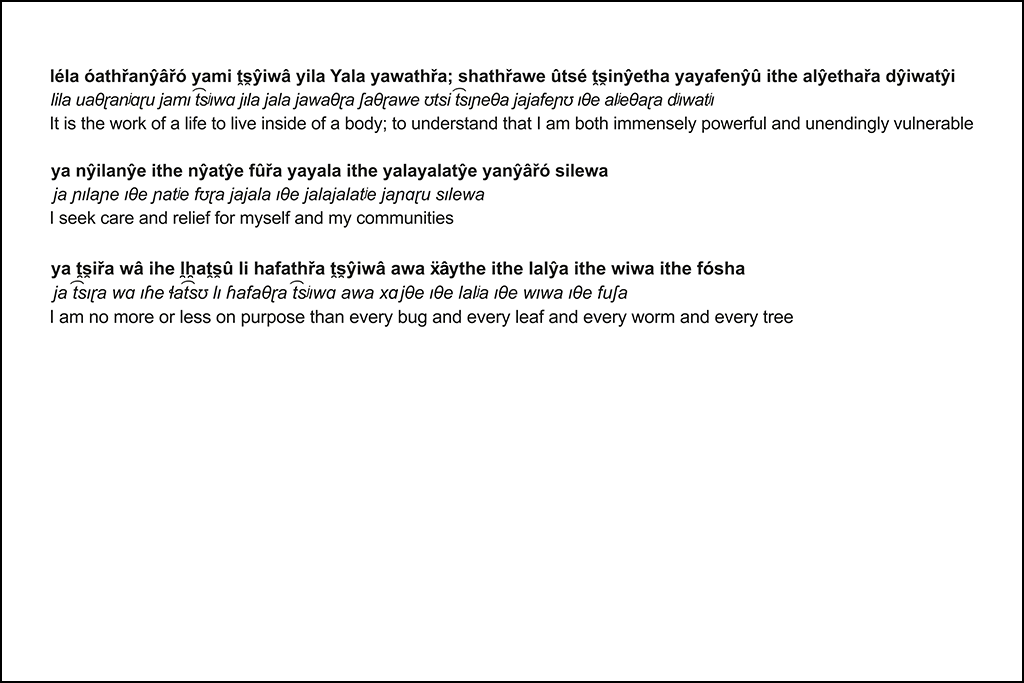

RA Walden, ẍây ithřa: a pledge (excerpt), site: Z4, 2021. Image courtesy the artist.

Audio Description – Transcript

Site: Z1

This work is displayed in landscape orientation in a 6 foot tall by 9 foot long lightbox with a black frame. The lower edge of this lightbox’s frame is at average standing height shoulder level.

The work consists of short statements that each appear as black text on a white background. The statements are presented in three lines in the following way: The full statement as a top line of bolded text written in the ẍây ithřa language. Below this is the statement written in phonetics and below this is the statement written in English translation.

The ẍây ithřa writing is printed all in lowercase letters and most words have accents marks above or below some letters. The phonetic text contains letters and symbols which are part of the phonetic alphabet.

The work in this lightbox has three statements covering just less than half of the available space. They take up the top left of the lightbox leaving the bottom right as blank white space. These will now be read out in ẍây ithřa using the phonetic as a guide and then this will be followed by their English translation.

ya dŷala litsónŷe ya yila dŷi ithe yanŷala lélanŷâřó wél̯h̯a iyewa

I let illness move through me in its own time and season

ya ẍây Yala ya ishal̯h̯a iyewa

I let the body lead me

nŷathřayala ithřatha ya t̯s̯ŷiwâ

Everybody is around me

End of Audio Description.

Site: Z2

This work is displayed in landscape orientation in a 6 foot tall by 9 foot long lightbox with a black frame. The lower edge of this lightbox’s frame is at knee level.

The work consists of short statements that each appear as black text on a white background. The statements are presented in three lines in the following way: The full statement as a top line of bolded text written in the ẍây ithřa language. Below this is the statement written in phonetics and below this is the statement written in English translation.

The ẍây ithřa writing is printed all in lowercase letters and most words have accents marks above or below some letters. The phonetic text contains letters and symbols which are part of the phonetic alphabet.

The work in this lightbox has two statements covering the top third of the available space leaving the lower two thirds as blank white space. These will now be read out in ẍây ithřa using the phonetic as a guide and then this will be followed by their English translation.

ya tesinŷû hâlé dŷisiya ya t̯s̯ŷiwâ, dŷidŷatha ya tesinyû t̯s̯ŷiwâ hâlé ya dŷidŷatha t̯s̯ŷiwâ

I am exactly who I am today, tomorrow I am exactly who I am tomorrow

ya Yala yanŷâřó nŷila, ya yalayala yanŷâřó nŷila, ya Yala yanŷâřó nŷila, ya Yala yanŷâřó nŷila

I take care of my body, I take care of my community, I take care of my planet, I take care of my home

End of Audio Description.

Site: Z3

This work is displayed in landscape orientation in a 6 foot tall by 9 foot long lightbox with a black frame. The lower edge of this lightbox’s frame is at doorknob height level.

The work consists of short statements that each appear as black text on a white background. The statements are presented in three lines in the following way: The full statement as a top line of bolded text written in the ẍây ithřa language. Below this is the statement written in phonetics and below this is the statement written in English translation.

The ẍây ithřa writing is printed all in lowercase letters and most words have accents marks above or below some letters. The phonetic text contains letters and symbols which are part of the phonetic alphabet.

The work in this lightbox has two statements covering the top third of the available space leaving the lower two thirds as blank white space. These will now be read out in ẍây ithřa using the phonetic as a guide and then this will be followed by their English translation.

léla tŷe Yala thóře yathete lawa yila ówamé dŷinŷâřó nŷařala ithe dŷalanŷâřó ithřadŷelaẍayeye

There is something to be found in the swamp of nonlinear time and the fog of disease

ya ẍatŷet̯s̯i yanŷâřó fûřa óathřa yanŷâřó ẍithe

I build my own expectations for my life

End of Audio Description.

Site: Z4

This work is displayed in landscape orientation in a 6 foot tall by 9 foot long lightbox with a black frame. The lower edge of this lightbox’s frame is at doorknob height level.

The work consists of short statements that each appear as black text on a white background. The statements are presented in three lines in the following way: The full statement as a top line of bolded text written in the ẍây ithřa language. Below this is the statement written in phonetics and below this is the statement written in English translation.

The ẍây ithřa writing is printed all in lowercase letters and most words have accents marks above or below some letters. The phonetic text contains letters and symbols which are part of the phonetic alphabet.

The work in this lightbox has three statements covering the top half of the available space leaving the lower half as blank white space. These will now be read out in ẍây ithřa using the phonetic as a guide and then this will be followed by their English translation.

léla óathřanŷâřó yami t̯s̯ŷiwâ yila Yala yawathřa; shathřawe ûtsé t̯s̯inŷetha yayafenŷû ithe alŷethařa dŷiwatŷi

It is the work of a life to live inside of a body; to understand that I am both immensely powerful and unendingly vulnerable.

ya nŷilanŷe ithe nŷatŷe fûřa yayala ithe yalayalatŷe yanŷâřó silewa

I seek care and relief for myself and my communities

ya t̯s̯iřa wâ ihe l̯h̯at̯s̯û li hafathřa t̯s̯ŷiwâ awa ẍâythe ithe lalŷa ithe wiwa ithe fósha

I am no more or less on purpose than every bug and every leaf and every worm and every tree

End of Audio Description.

Reading Stations

Each lightbox is accompanied by a casual reading station with prompts and booklets–designed to encourage slow and thoughtful engagement with the stanzas on display. Visit all four lightboxes to explore lexicon charts themed around Body, Care, Idioms, and Pain. The publications below include extended vocabulary, information on grammar, and notes on translation to support learning to read, speak, and understand ẍây ithřa. Group learning is encouraged! Booklets available for download as PDFs below.

Book I/IV: Lexicon (subgroups)

Book II/IV: Lexicon (ẍây ithřa to English)

Book III/IV: Lexicon (English to ẍây ithřa)

Book IV/IV: Grammar + Bibliography

ẍây ithřa: a pledge

Sites Z1-Z4 on the map

Across the four Blackwood lightboxes on UTM campus, ten statements illustrate the foundational concepts of ẍây ithřa (a pledge), a language created by artist RA Walden. Named after the title of this text, ẍây ithřa was developed over several months in close collaboration with linguist Margaret Ransdell Green. It emerged in response to the ableism and limits of the English language, and features a lexicon of over 300 words, with its own morphosyntax, phonology, and an expanding set of idioms. Drawing from histories of queering language–from argots and cants to anti-languages and constructed languages in science fiction–Walden brings fluidity, ease, and “access intimacy” to those in sick, disabled, and trans bodies. Here, world-building is not a tool for an imagined future, but an embodied methodology for the present.

In ẍây ithřa, the word Yala holds multiple meanings: body, home, and planet earth. While translated as “body” for readability, its meaning encompasses both the physical self and celestial forms. ẍây ithřa expresses bodily experiences through earthly elements–a sharp pain might be described as ẍâwehethřathařa, a rock tumbling down a mountain, while the easing of pain is wél̯h̯athřafóshâtŷama, wind caressing trees.

Time in ẍây ithřa is nonlinear, circular, and simultaneous–aligned with “crip time,” (1) a concept introduced by feminist disability scholar Alison Kafer. Crip time resists productivity and profit-driven deadlines, instead centring slowness, intuition, and decisions attuned to the body’s rhythms.

(1) See ‘Notes for “Sick Time, Sleepy Time, Crip Time: Against Capitalism’s Temporal Bullying” in conversation with the Canaries’: Taraneh Fazeli, ‘Six Ways of Looking at Crip Time’: Ellen Samuels, ‘Feminist, Queer, Crip’: Alison Kafer.

The Blackwood

University of Toronto Mississauga

3359 Mississauga Road

Mississauga, ON L5L 1C6

[email protected]

(905) 828-3789

The galleries are open. Hours of operation: Monday–Saturday, 12–5pm.

Facebook | Twitter | Instagram

Sign up to receive our newsletter.

The Blackwood is situated on the Territory of the Mississaugas of the Credit, Seneca, and Huron-Wendat.