Adrian Blackwell creates discourse-machines: spaces of intellectual generosity, where bodies congregate, they move, think, and speak together, and they lay claim to a certain space as public space.1 Blackwell’s commissioned project Furnishing Positions provides the falsework laying claim to the Blackwood Gallery as a public space. It is a modular sculpture that is reconfigured six times throughout the exhibition; it is a broadsheet published once every two weeks; and it is a set of conversations between contributors to the broadsheets. With Furnishing Positions, Blackwell stages the paradox of public space according to six encounters: affinity and disagreement, representation and presentation, people and things, materiality and immateriality, privacy and publicity, and city and urbanization. By thinking of public space in terms of its essential polarities, a field of contestation is opened between extremes, providing a conceptual space for discussion and disagreement.

Project Description

with Abbas Akhavan, Eric Cazdyn, Greig de Peuter, Kanishka Goonewardena, Karen Houle, Mary Lou Lobsinger, Dylan Miner, Paige Sarlin, Scott Sørli, Charles Stankievech, Kika Thorne, cheyanne turions.

Since the financial crisis of 2008, we have watched a resurgence of political demonstrations and occupations in the Middle East, North Africa, China, Greece, Spain, the United Kingdom, and North America that have reanimated the concept of public space. In each case, citizens gathered in squares and streets, in opposition to today’s political economy of austerity and inequality. For over thirty years neoliberalism has effected a two-pronged assault on public space: on the one hand it has been transformed almost entirely into a space of capital flow, and on the other it has become more heavily surveilled. These two forms of enclosure—one by the market, the other by the state—appear as opposites, but they function as complementary dimensions of neoliberalism, which pursues a relentless opening of markets while intensifying society’s social and economic disparities.

To better understand this contemporary situation it is worth returning to Jürgen Habermas’s concept of the “public sphere”2 in order to sketch a provisional definition of “public space.” Habermas conceived of the public sphere as a mediating or communicating zone between public authority and the private sphere, emerging in an essentially sympathetic relation to new forms of bourgeois governance in Europe. It was in this sense that the bourgeois public sphere could strive to operate as a locus of rational communication between the two other realms and our conception of “publicness” in both its senses (public authority and the public sphere) is tied to the invention of bourgeois private property.

The emergence of the modern private property regime was a profound event, because it severed the obligations that existed within earlier land-use regimes to create a form of land that is on the one hand open to all and alienable at any time, and on the other, owned absolutely and entirely monopolizable. The construction of this historically specific form of private space was coincident with the production of a repertoire of new spaces of public authority, such as urban avenues, parks, government buildings, libraries, prisons, and hospitals, which were all produced to solidify social control. Capitalism is thus founded on the co-production of two realms: the entirely unequal system of private property, and spaces of public authority whose function is to surveil and normalize capitalist subjects.

If we apply the emergent concepts of private property and public authority to space, we can think of public space as analogous to the public sphere, as a physical space in which private people come together in order to question both the state and the economy. In this conception, we end up with three spaces: private economic space, spaces of public authority, and “public spaces.” Given that all space in democratic capitalist society is legally controlled through the rights of sovereign or private property, public space must always be constructed on top of a space governed either by the private economy or public authority. Public space is always an appropriation, a layering of a political space over legal space. This is clear when we take a quick glance at the physical spaces in which publics have asserted their power and produced new democratic knowledge, from public squares to universities, coffee houses, and private homes. These are spaces built either by public authorities or private economic agents (or some combination of the two); public spaces only appear within them when they are actively constructed.

So what exactly is produced when a public space is made? Insofar as it is a thoroughly capitalist institution, a locus of criticism internal to capitalism, public space always involves the construction of a paradox within physical space. It is not that public space today appears contradictory, rather that spaces of public authority and private economy are themselves contradictory, and public space is the construction of a spatial and material argument that brings their contradictions to light.

Furnishing Positions is a sculpture, a broadsheet, and a set of conversations that will stage the paradox of public space according to six encounters: affinity and disagreement, representation and presentation, people and things, materiality and immateriality, privacy and publicity, and city and urbanization. By thinking of public space in terms of its essential polarities, a field of contestation is opened between extremes, providing a conceptual space for discussion and disagreement.

—Adrian Blackwell

-

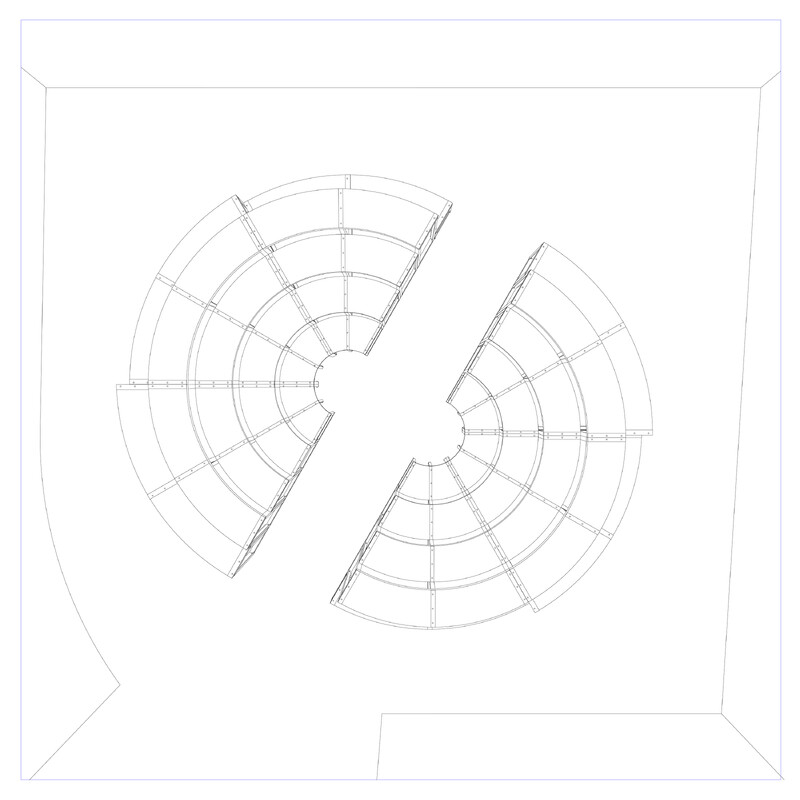

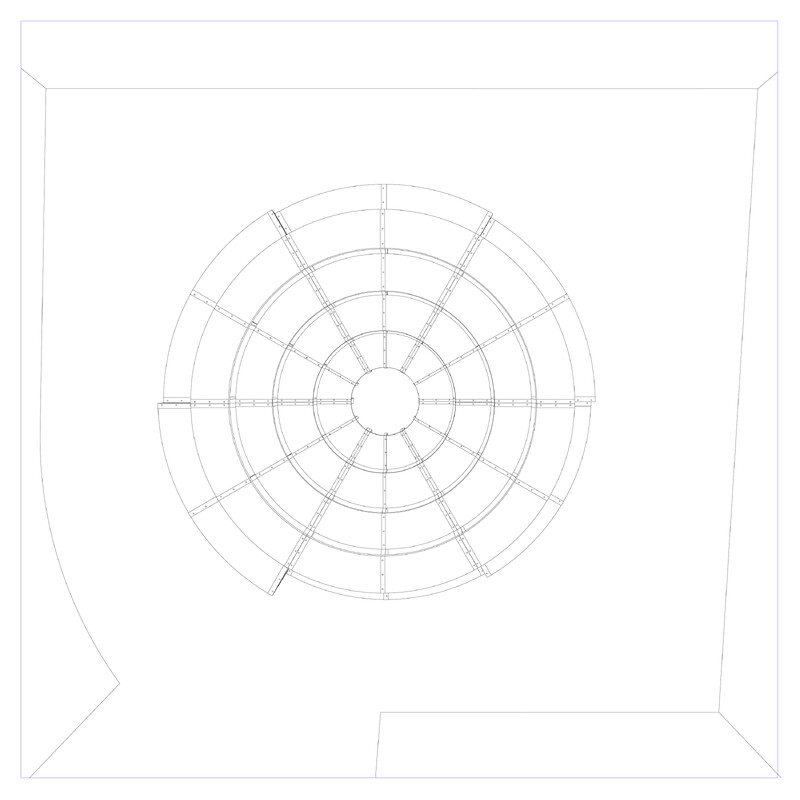

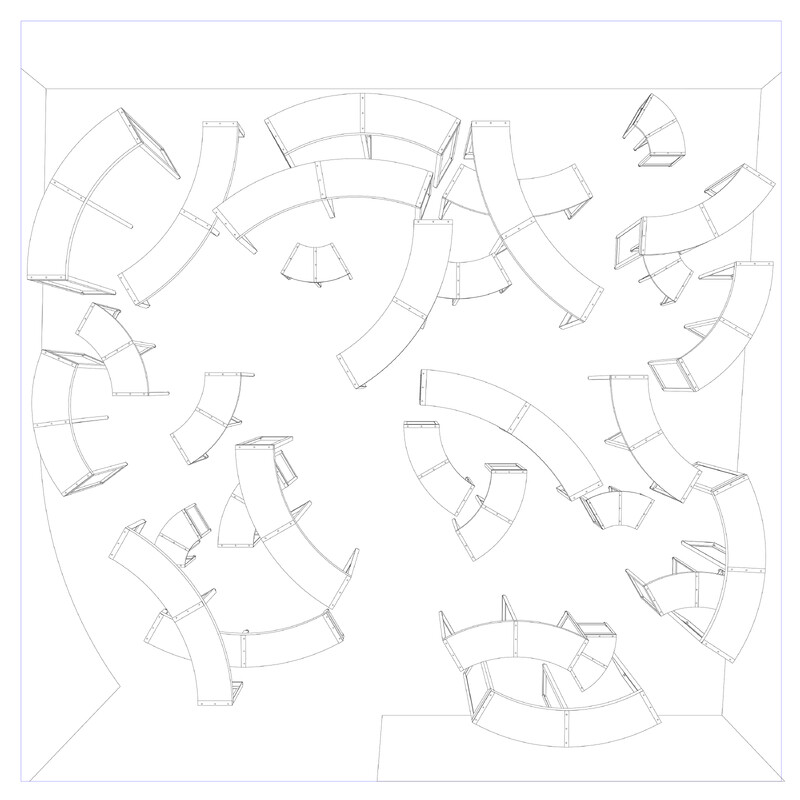

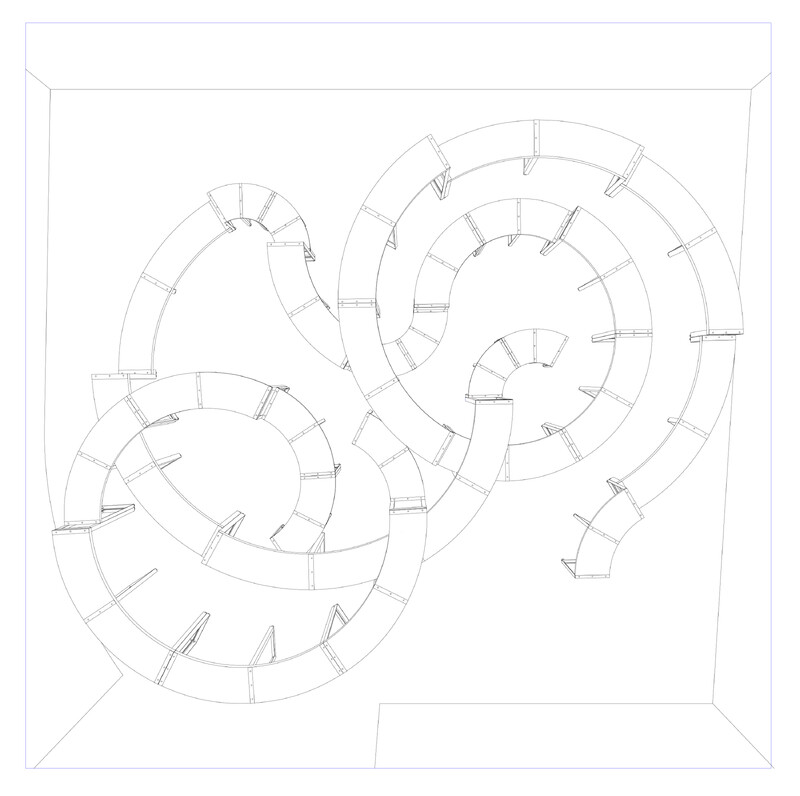

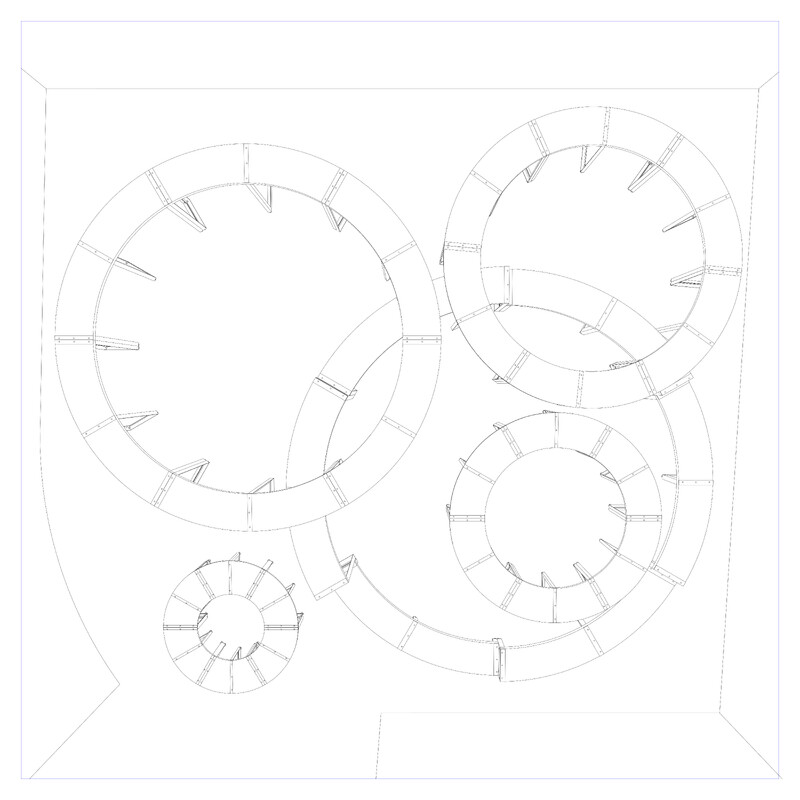

Adrian Blackwell, Furnishing Positions, 2014. September 15 - 28, 2014. -

Adrian Blackwell, Furnishing Positions, 2014. September 30 - October 13, 2014. -

Adrian Blackwell, Furnishing Positions, 2014. October 15 - 26, 2014. -

Adrian Blackwell, Furnishing Positions, 2014. October 28 - November 9, 2014. -

Adrian Blackwell, Furnishing Positions, 2014. November 11 - 23, 2014. -

Adrian Blackwell, Furnishing Positions, 2014. November 25 - December 7, 2014. -

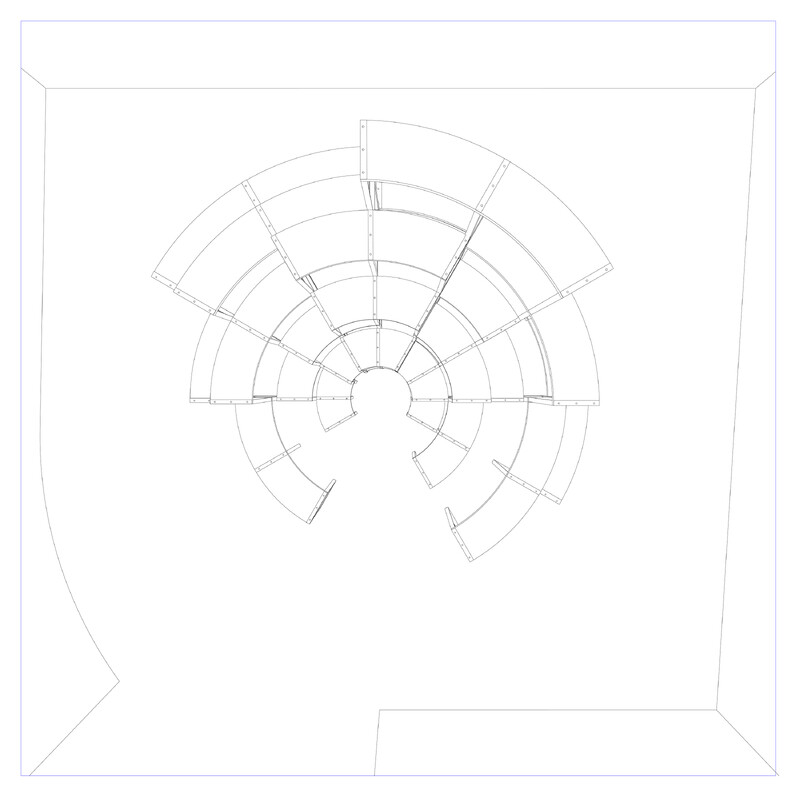

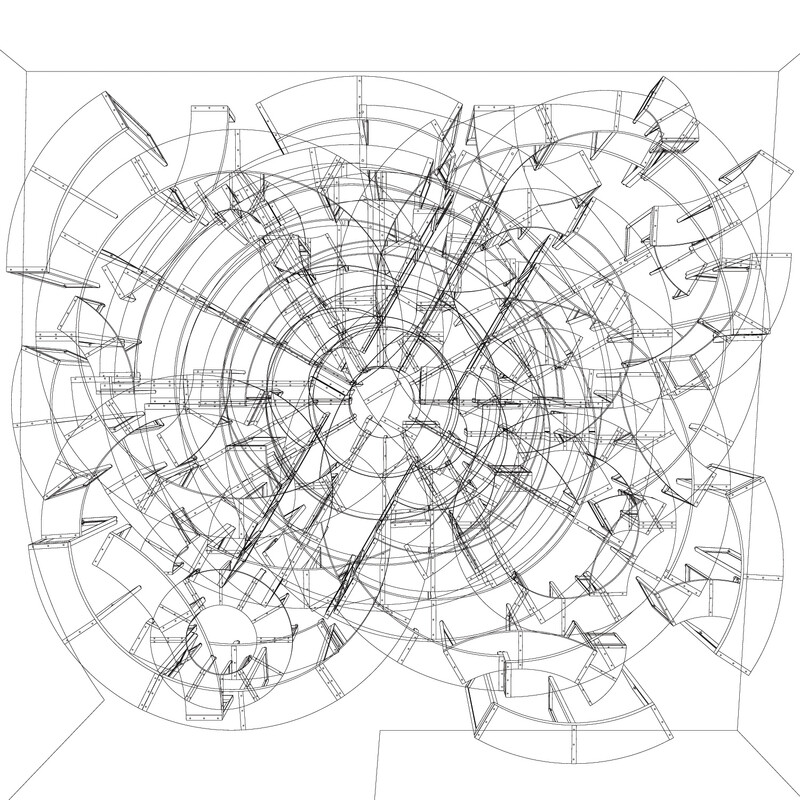

Adrian Blackwell, Furnishing Positions, 2014. Overlay of six drawings by Matthew Hoffman.

-

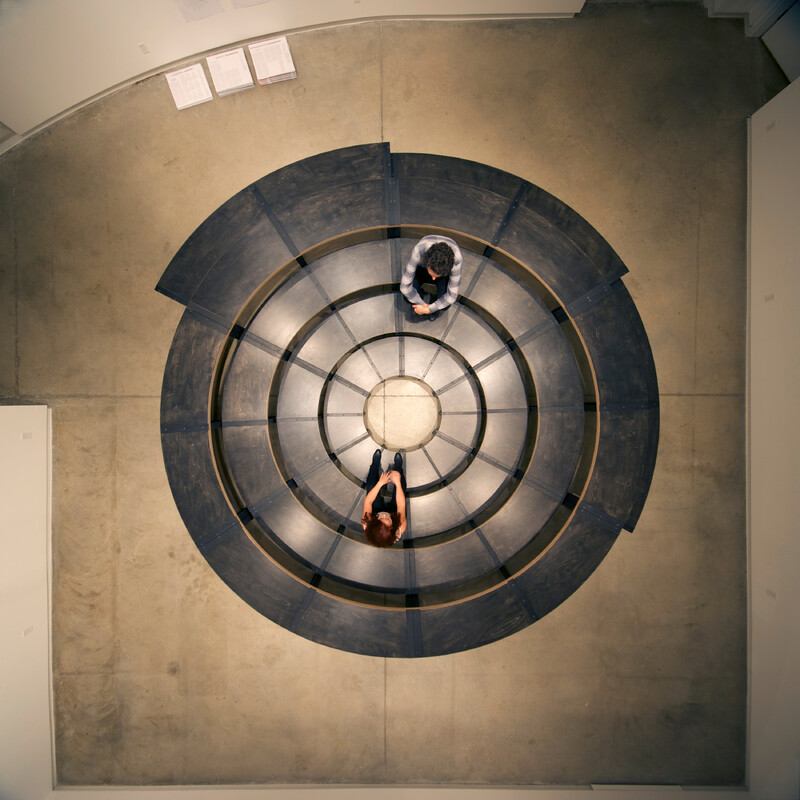

Adrian Blackwell, Furnishing Positions, 2014. Installation view. Photo: Blackwood Gallery Staff. -

Adrian Blackwell, Furnishing Positions, 2014. Installation view. Photo: Blackwood Gallery Staff. -

Adrian Blackwell, Furnishing Positions, 2014. Installation view. Photo: Blackwood Gallery Staff. -

Adrian Blackwell, Furnishing Positions, 2014. Installation view. Photo: Blackwood Gallery Staff. -

Adrian Blackwell, Furnishing Positions, 2014. Installation view. Photo: Blackwood Gallery Staff. -

Adrian Blackwell, Furnishing Positions, 2014. Installation view. Photo: Blackwood Gallery Staff.

-

Adrian Blackwell, Furnishing Positions, 2014; Allora & Calzadilla, Vieques Videos, 2004-2005. Installation view. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid. -

Adrian Blackwell, Furnishing Positions, 2014; Allora & Calzadilla, Vieques Videos, 2004-2005. Installation view. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid. -

Adrian Blackwell, Furnishing Positions, 2014; Mary Mattingly, House and Universe, 2014. Installation view. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid. -

Adrian Blackwell, Furnishing Positions, 2014. Installation view. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid. -

Adrian Blackwell, Furnishing Positions, 2014. Installation view. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid. -

Adrian Blackwell, Furnishing Positions, 2014; Mary Mattingly, House and Universe, 2014. Installation view. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid. -

Adrian Blackwell, Furnishing Positions, 2014; Mary Mattingly, House and Universe, 2014. Installation view. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid. -

Adrian Blackwell, Furnishing Positions, 2014; Mary Mattingly, House and Universe, 2014. Installation view. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid. -

Adrian Blackwell, Furnishing Positions, 2014. Installation view. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid. -

Adrian Blackwell, Furnishing Positions, 2014. Installation view. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid. -

Adrian Blackwell, Furnishing Positions, 2014. Installation view. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid. -

Adrian Blackwell, Furnishing Positions, 2014. Installation view. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid. -

Adrian Blackwell, Furnishing Positions, 2014; Mary Mattingly, House and Universe, 2014. Installation view. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid. -

Adrian Blackwell, Furnishing Positions, 2014; Mary Mattingly, House and Universe, 2014. Installation view. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid. -

Adrian Blackwell, Furnishing Positions, 2014. Installation view. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid. -

Adrian Blackwell, Furnishing Positions, 2014. Installation view. Photo: Toni Hafkenscheid.

Furnishing Positions

Blackwell’s research focuses on the intertwined problems of public space and private property. Publications include: “Forms of Enclosure in the Instant Modernization of Shenzhen” in Volume and “What is Property?” in the Journal of Architectural Education. He has been a visiting professor at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design and is an Assistant Professor at the University of Waterloo School of Architecture. He was a member of Toronto’s Anarchist Free School and the Toronto School of Creativity and Inquiry, and is an editor of the journal Scapegoat: Architecture / Landscape / Political Economy.

Furnishing Positions consists of a set of thirty structurally similar pieces of furniture; each has steel legs and a plywood top. The furniture has four different heights: 30cm, 60cm, 90cm, and 120cm, roughly the heights of a bench, a table, a counter, and a ledge. Each piece is curved to form one-sixth of a circle, so that six pieces can assemble to form a ring of various heights. The circles are adjacent and concentric so that the furniture can be assembled to form a circular amphitheatre, but it can also be arranged in an almost infinite set of other configurations. For the Blackwood Gallery, the sculpture will be reconfigured six times and will function as furniture on which to stage a set of public conversations on the constitutive paradox of public space. The sculpture embraces historian of science Bruno Latour’s assertion that all things are assemblages, strange and monstrous hybrids of diverse elements. Not least among these monsters, society itself is made up of the most complex composition of people and things.1 What this social monster needs are places of assembly that can gather together its various parts: people, their desires, and their matters of concern. Furnishing Positions is designed to catch and assemble these heterogeneous elements in its changing forms.

1) Bruno Latour, “From Realpolitik to Dingpolitik,” in Making Things Public, ed. Bruno Latour and Peter Weibel (Karlsruhe: ZKM/Center for Art and Media, and Cambridge: MIT Press, 2005), 38.

The Blackwood

University of Toronto Mississauga

3359 Mississauga Road

Mississauga, ON L5L 1C6

[email protected]

(905) 828-3789

The galleries are open. Hours of operation: Monday–Saturday, 12–5pm.

Facebook | Twitter | Instagram

Sign up to receive our newsletter.

The Blackwood is situated on the Territory of the Mississaugas of the Credit, Seneca, and Huron-Wendat.